Portraiture evidently suited Jan Lievens (1607-1674) well. His earliest independent work, according to Jan Jacobsz Orlers (1570-1646), was a likeness of his mother that earned him immediate local fame.1 Later, Constantijn Huygens (1596-1687) encouraged the young Lievens in the same direction. Despite his initial misgivings, Lievens produced a striking and memorable likeness of the Stadholder’s secretary, even evoking his preoccupied state of mind (fig. 2).2 It was certainly the right specialty for his subsequent move to London (1632), where Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641) was kept busy with portrait commissions. Lievens did not break through the market there, however, and proceeded to Antwerp (1634). He evidently sought courtly patronage, such as he later achieved with commissions in The Hague and Berlin3. Recently, a portrait has resurfaced that strongly suggests that he did achieve at least one high-level commission for a portrait painting during his nine years in the city on the Scheldt.

A Rediscovered Portrait

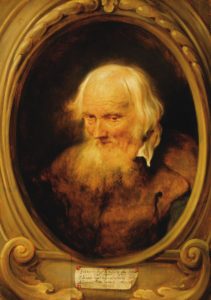

In November 2020, a bust-length portrait of a mature man in near profile appeared in a mixed sale in Vienna, as from the “Circle of Bartholomeus van der Helst” (fig. 1).4 This was not an overestimation, as the high quality of the work was evident, but it was nonetheless inaccurate. The handling displays none of the smooth and broad application typical of Van der Helst, nor his typical dynamism of sweeping lines. Closer inspection reveals a remarkable, even dazzling range of textural effects, especially in the frizzy hair but also in the skin, beard stubble, and fabric. These are choregraphed to enhance the sitter’s presence, in a grand presentation closely aligned with the work of a different Dutch artist, namely Jan Lievens, and more specifically that of his Antwerp period, from 1634 to 1644. It was purchased at the sale by David and Michelle Berrong-Bader and was cleaned by Michel van de Laar, revealing minor losses, and the possible remnants of a monogram (fig. 3). This striking painting is currently on loan to the Rembrandt House Museum.

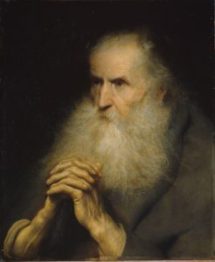

It is perhaps not very surprising that this work went largely unrecognized at the sale, as there are no directly comparable painted portraits by Lievens from the same period. Instead the most relevant paintings are found among Lievens’s tronies from the period, most significantly the Old Man in Schwerin (fig. 4), with its striking rendering of a full beard in layers of fine strokes in opaque paint, some of it dragged5 This striking technique employs physical texture, known as kenlijkheid,6. to catch the eye and draws these lines forward, conjuring an open, nest-like structure for the beard. It provides a direct parallel to the handing of the hair at the side of the head in the Bader-Berrong painting (figs. 5, 6). The effect is enhanced by the use of black, grey, white and ochre for the various layers of depth. We already see a leadup in the colour play of cool greys and ochres in Lievens’s signal and final masterpiece in Leiden, the Job on the Dungheap of 1631, now in Ottawa,

7 and the closely related Penitent Magdalene in the Bader Collection at Queen’s University in Kingston.8 These brilliant technical experiments carried out in friendly competition with Rembrandt in Leiden, until 1631, still echo around six years later in the newly resurfaced portrait.

|

At the same time, the impact of Anthony van Dyck’s portraiture studied in London and Antwerp also reveals itself. The gently undulating surface and fluid, sweeping contours of the collar and edges of folds of the jerkin depart from the stiff solidity of the Leiden years, witnessed in the Huygens portrait. We see this development already in Lievens’s drawn portrait of his friend and fellow artist in Antwerp, the still life specialist Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606-1684: fig. 7).9 In his Head of an Old Man in New Orleans, which bears a monogram and date of 1640, Lievens appears to have gone even further in adopting Van Dyck’s manner (fig. 8).10 He has moved further away from the flamboyant textural effects of his Leiden years, and towards a smoother idealization of the figure. Even accounting for possible wear, the beard and hair no longer show the prickly, toothy effect of the webs of thin opaque dragged strokes in the Schwerin and Bader-Berrong paintings; these can therefore be placed earlier. The soft and atmospheric handling approximates another male tronie, in the Bader Collection in Kingston, which must also date around 1640.11

|

The date and place of a portrait often find reflection in the fashion represented. The most prominent element in the Bader-Berrong portrait is the broad, flat collar. It is largely the same as worn in several portraits drawn by Lievens in Antwerp around 1636/37, including that of Jan Davidsz. de Heem (fig. 7), and of Adriaen Brouwer (1603-1638). 12 It is quite different from the lace collars that dominate elite male portraiture in Amsterdam and London in the second half of the 1630s. When Lievens portrayed Constantijn Huygens in a drawing on a visit to Leiden in 1639, it was, by contrast, in a lace collar.13 Yet it appears to have been a general preference for portrait representations in each location, and that behind the scenes, in real life, lace and flat collars were both worn in both locations. Marieke de Winkel speculates that the preference for flat collars in Antwerp portraits may even have been dictated by painters who saw the surface of the flat collar as better suited to the fluid lines and undulating surfaces characterizing local painting fashion in general and who may have been disinclined to labour over the details of lace.14

Lievens was himself otherwise not shy when it came to description of detail. He devoted special attention to the man’s striking jerkin peering out from under the collar. Liquid strokes of thin black and ochre paint describe a stiff textile with a reflective surface pattern, likely brocade. 15 The artist occasionally employed such strokes as part of his demonstrative mastery of brush and paint, as he did in the metallic trim on the front of the doublet of the young merchant Adriaen Trip, painted soon after Lievens moved to Amsterdam in 1644 (figs. 9 and 10).

The kind of imposing presentation in the Bader-Berrong painting was favoured by Lievens, as already observed by Huygens soon after he encountered the artist in a visit to Leiden in 1628.16 Wearing the shoes of the liefhebber, or art lover, the secretary to the stadholder was exercising powers of observation and analysis in the well-known passage of his autobiography contrasting Lievens’s inclinations with Rembrandt’s talent for conjuring grand emotions even in small figures. His characterization of Lievens was later echoed in the inscription on the print after Anthony van Dyck’s portrait of the artist: “Pictor Humanarvm Figvrarem Maiorvm”(Painter of Grand Human Figures).17

Already his earliest known paintings fill the frame with the subject. This can also be said of his first known formal portrait, depicting Huygens himself (fig. 2).18 He forms a stable and imposing pyramidal shape in the picture plane, with his rich black cloak billowing out to the right and left. The overall focus falls on the sharply defined eyes, with their fixed gaze to the right, emphasized by tonal contrast of iris against the whites of the eyes, and shadows cast by the light from the side.

Despite Huygens’s high praise, Lievens did not right away attract substantial commissions for painted portraits. An intriguing pen portrait of King Charles I may represent a fleeting high point of his stay in London, although Orlers claims he also painted a portrait of the British royal family.19

Commissions for painted portraits appear to have represented a threshold Lievens found difficult to cross in his first ventures outside the United Provinces. Only one example from the Antwerp period (1634-1644) was previously known, and it is notable for its eccentricity (fig. 11). Egidius Petrus de Morrion is shown peering through an illusionistic carved frame, bearing an illusionistic piece of paper identifying the sitter and claiming an astonishing age of 112 years. The cartouche is completed with the artist’s signature and a date of 1637. Strangely, we know nothing else about De Morrion. The Latinized first and second names (for Gillis and Pieter or Peter) strongly suggest a scholarly profile, and the man’s sharp gaze and smile evoke intellect and wit. It could be that he was portrayed for reasons other than his extreme age. But the portrait does not project high social or political status, and thus falls short of the court patronage ambitions that drew Lievens to London and Antwerp.

From the 1630s we mainly have drawn portraits, mostly of fellow artists. In Antwerp, he drew striking portraits of painters Adriaen Brouwer and Jan Davidsz. De Heem, who, judging by the inclusion of all three in Brouwer’s famous Smokers in New York, were his friends.20 His portrait prints of these and other acquaintances, including flower painter Daniel Seghers, were inspired by Van Dyck’s series of famous men and women, the Iconography, and likely intended to form part of a similar series.21

Curiously, Lievens did manage to secure high level patronage for drawn portraits. In terms of characterization of the sitter, the work from these years most closely related to the Bader-Barrong portrait is a drawing of the military captain Hieronymus de Bran (in a lace collar, exceptionally: fig. 12).22 It appears to have been intended for inclusion in the Iconography.23 The context must have been similar for both: a portrait of a man in a high political or military position, as their formal poses exude fortitude. The gold chain both men wear speaks of a gift of favour from a King or Emperor, usually awarded for service, often political or military but sometimes also literary or artistic. We do not see a medallion identifying the ruler. We also do not have any other attributes or clear connections leading to a specific identity for the handsome sitter here. It is tempting to look to Lievens’s most prominent commissions for history paintings in these years, but these were for the Jesuits, and were obtained through his father-in-law, a prominent Antwerp sculptor already working on the same projects.24 An impressive drawn portrait of a man has been identified as Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel (1585-1646), the noble collector who fled to Antwerp in the wake of the demise of Charles I.25 The expressive head betrays a downcast sentiment, in line with his distressed situation in exile, in Antwerp, around 1643. By this time, Lievens was probably already looking to move on in search of patronage.

A comparably high social status is represented in the portrait now on loan to the Rembrandt House Museum. The sitter gazes slightly upwards, and seems to sets his sights on higher aspirations, probably more worldly than spiritual, as Lievens did. A similar, slightly elevated gaze occurs in Lievens’ portrait of Huygens (fig. 2) and subsequently in several tronies, in which the artist also experimented with a grand effect.26 It reflected his image of himself as well. His confident attitude rubbed several people the wrong way, first of all Huygens himself, but also the Earl of Ancram (c. 1579-1655), who wrote with clear irritation at Lievens’s claim to be the best painter in all of Northern Europe.27 Status mattered to Lievens, in ways it did not to his friend Rembrandt, who turned out one bourgeois portrait after another after arriving in Amsterdam. Around 1637, in Antwerp, Lievens evidently found his moment, and later in the Northern Netherlands he would indeed attract commissions, also for portraits, at the highest levels.

David de Witt is Senior Curator at The Rembrandt House Museum

My thanks to Stephanie Dickey for her careful reading of this article, and for her valuable insights and suggestions.

- Jan Jacobsz. Orlers, Beschrijvinge der Stadt Leyden, 2nd ed., Leiden, 1641, p. 376.

- See the translation from the original Latin: “Constantijn Huygens on Lievens and Rembrandt,” in: Arthur K. Wheelock et al., Jan Lievens. A Dutch Master Rediscovered, exh. cat. Washington: National Gallery of Art; Milwaukee: Milwaukee Art Museum; Amsterdam: Museum Het Rembrandthuis, 2008-2009, p. 287.

- See: Arthur K. Wheelock, “Jan Lievens: Bringing New Light to an Old Master,” in: Wheelock, Lievens (see note 2), pp. 13-23; and: Lloyd DeWitt, Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674), Ph.D. dissertation, University of Maryland, 2006: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277127128_Evolution_and_Ambition_in_the_Career_of_Jan_Lievens_1607-1674

- Property from Aristocratic Estates and Important Provenance, Vienna (Dorotheum), 8 September 2020, lot 59 (as Circle of Bartholomeus van der Helst).

- Werner Sumowski, Gemälde der Rembrandt-Schüler, Landau, vol. 5, 1990, p. 3109, no. 2127, ill. p. 3279

- Ernst van de Wetering, Rembrandt: the Painter at Work, Amsterdam, 1997, pp. 182-185.

- Jan Lievens, Job in his Misery, monogrammed and dated 1631, canvas, 171.5 x 148.6 cm, Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada (4093). See Lloyd DeWitt in Wheelock, Lievens (see note 2), pp. 130-131, no. 25 (colour illus.).

- Jan Lievens, The Penitent Magdalene, c. 1631. Canvas, 63.5 x 49.5 cm. Kingston, Agnes Etherington Art Centre, gift of Dr. and Mrs. Alfred Bader, 1975 (18.126). See David de Witt in Wheelock, Lievens, pp. 128-129, no. 24 (colour illus.).

- Portrait of Jan Davidsz. de Heem, c. 1635/37, black chalk with some white body colour, 265 x 201 mm, London, British Museum (1895,0915.1199); Werner Sumowski, Drawings of the Rembrandt School, New York, vol. 7 (1983), pp. 3682-3683, no. 1652x (illus.).

- See entry by Lloyd DeWitt in: Wheelock, Lievens (see note 2), pp. 154-155, no. 38 (colour illus.).

- Jan Lievens, Head of a Bearded Old Man, c. 1640. Panel, 55 x 43 cm (oval), Kingston, Agnes Etherington Art Centre, gift of Alfred and Isabel Bader. See: David de Witt, The Bader Collection: Dutch and Flemish Paintings. Kingston, 2008, p. 198, no. 117 (colour illus.).

- Jan Lievens, Portrait of Adriaen Brouwer, c. 1635/37, black chalk with touches of pen in black, 221 x 185 mm, Paris, Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt (1203); Sumowski, Drawings (see note 9), pp. 3356-3357, no. 1594 (illus.).

- Jan Lievens, Portrait of Constantijn Huygens, 1639, black chalk with touches of pen in brown, 238 x 174 mm, London, British Museum (1836.8.11.342); see Wheelock, Lievens (see note 2), p. 242-243, no. 103 (colour illus.).

- Email correspondence with the author, 9 September 2020.

- My thanks to Stephanie Dickey for this information (email, 31 October 2022), confirmed by Marieke de Winkel.

- See Wheelock, Lievens (see note 2), p. 286.

- Lucas Vorsterman, after Anthony van Dyck, Portrait of Jan Lievens, c. 1630-1645, engraving, 241 x 158 mm, in 6 states, for the series: Icones Principorum Vivorum Doctorum Pictorum…; see: Marie Mauquoy-Hendrickx, L’Iconographie d’Antoine van Dyck, 2nd ed., Brussels, 1991, vol. 1, p. 155, no. 85; vol. 2, pl. 54 (illus.).

- Wheelock, Lievens (see note 2), pp. 112-113, no. 112 (colour illus.).

- Jan Lievens, Portrait of Charles I, pen in brown, 183 x 140 mm, Turin, Biblioteca Reale (D. C. 16365); Sumowski, Drawings (see note 9), pp. 3898-3899, no. 1754xx, (illus.); Orlers, Beschrijvinge (see note 1), pp. 375-377.

- Karolien de Klippel, “Adriaen Brouwer, Portrait Painter: New Identifications and an Iconographic Novelty,” Simiolus 30 (2003), pp. 196-216.

- Stephanie Dickey, “Jan Lievens and Printmaking,” in Wheelock, Lievens (see note 2), pp. 60-62. On the Iconography, see Mauquoy-Hendrickx, Iconographie (see note 7).

- DeWitt, Evolution (see note 3), p. 192, illus. fig. 144 (Lievens c. 1635/43, H. de Bran); attribution by Werner Sumowski: written correspondence with the museum of 28 July 1986; and: Drawings of the Rembrandt School, vol. 12 (Addenda), Leiden (forthcoming), no. 3104x.

- See Mauquoy-Hendrick, Iconography (see note 17), vol. 1, p. 214, no. 190; vol. 2, pl. 119.

- See DeWitt, Evolution (see note 3), pp. 160-164.

- Jan Lievens, Portrait of Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, black and red chalk, 180 x 140 mm, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett (KdZ 5869); Wheelock, Lievens (see note 2), p. 249, no. 109 (colour illus.).

- Jan Lievens, Profile Head of an Old Woman in Oriental Dress, c. 1630, panel, 43.2 x 33.7 cm, Kingston, Agnes Etherington Art Centre, gift of Alfred and Isabel Bader, 2005 (48-002). See entry by David de Witt in Wheelock, Lievens (see note 2), pp. 122-123, no. 21 (colour illus.).

- Letter to his son the Earl of Lothian, May 1654: Correspondence of Sir Robert Kerr, First Earl of Ancram, and His Son William, Third Earl of Lothian, vol. 2, London, 1875, p. 383; C. Hofstede de Groot, “Hollandsche Kunst in Schotland,” Oud Holland 11 (1893), p. 214.