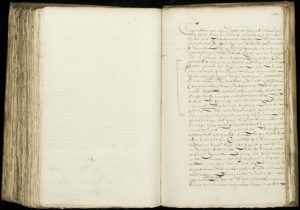

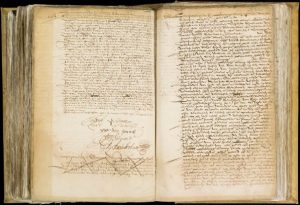

The painted oeuvre of Rembrandt has to a certain extent been delimited by the Rembrandt Research Project. Although the conclusions there formulated are not always shared by all, the discussion generally concerns works that are long known. The resurfacing of a completely unknown painting is extremely rare. Likewise, the emergence of an archival discovery is not an everyday occurrence. The archival researches of Abraham Bredius (1855-1946), Isabella van Eeghen (1913-1996), Bas Dudok van Heel (1938) and others have unearthed a rich treasure trove concerning the life and work of Rembrandt and his milieu. The very extensive Amsterdam Notarial Archive consistently showed itself to be a nearly inexhaustible source for drawing historical links and making new discoveries (fig. 1). Of course, new research also encountered known material. Dudok van Heel remarked in 1987 that a red or blue pencil crayon line meant that Bredius had beat him to it.1 Other researchers also left their traces (figs. 2, 3).

Leafing by hand through the protocols or close reading of microfilms is very time consuming and researchers followed the path dictated by their research. Already in Bredius time it was clear that some notaries were more regularly involved with art and artists; those parts of the archive offered better chances. Going through the entire notarial archive, which extends to 3.5 kilometres of bookshelves and covers a period of nearly 350 years (1578-1915), was utterly impossible in human terms, even if research was limited to a timespan of ten or twenty years. One remained dependent on the card index on individual names and subjects compiled by Simon Hart (1911-1981) and other archive employees (which covered around 5% of the entire archive), serendipity or lucky finds while doing other research.

All Amsterdam Records (Alle Amsterdamse Akten)

Searching by hand or microfilm through the notarial archive is increasingly becoming a part of the past. Starting in 2016, with the project Alle Amsterdamse Akten of the Amsterdam City Archives, and then indexed by volunteers. By October 2021 there were 8,8 million scans available on-line, mainly of documents from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It is anticipated that by the end of 2021 the entire seventeenth-century section of the archive will be digitized, including the protocols with water and fire damage. This will turn out to be a treasure trove of information that has hitherto hardly been unlocked or used, a wealth of data from a period in which Amsterdam was one of Europe’s largest and most important cities. Thanks to its unique historical value, the archive was included in 2017 in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register. Current accessibility is limited to indexes by date, document type, individual names and locations outside of Amsterdam. The results are available to all through a search function on the website of the City Archives.2 The index already includes the impressive amount of 3.1 million individual names, a number that is steadily growing. Compared to the old boxes of index cards from the twentieth century, the Alle Amsterdamse Akten project represents an enormous leap ahead.3 It is however not yet possible to search the archive by word, so that human recognition, just as before, forms the basis for indexing. But here also changes are taking place. From March 2021 the Amsterdam City Archives hosts a search function in which documents transcribed by the computer program Transkribus are completely searchable using HTR (Handwritten Text Recognition).4 Although currently limited to a number of 300,000 documents, about 1.5% of the estimated 20 million scans that the notarial archive comprises, it is already evident that this combination of digital technology will revolutionise the use of written documents for historical research. The Rembrandt document described in this article is a direct result of this technology.

Two New Rembrandt References

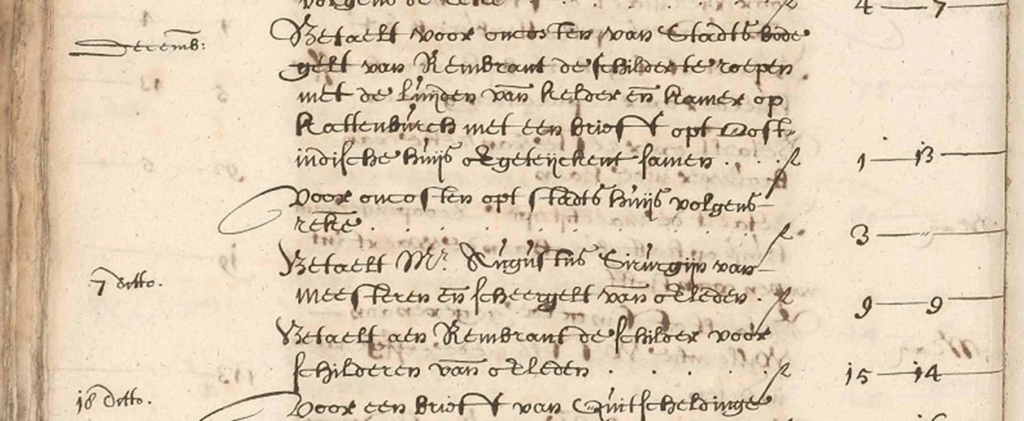

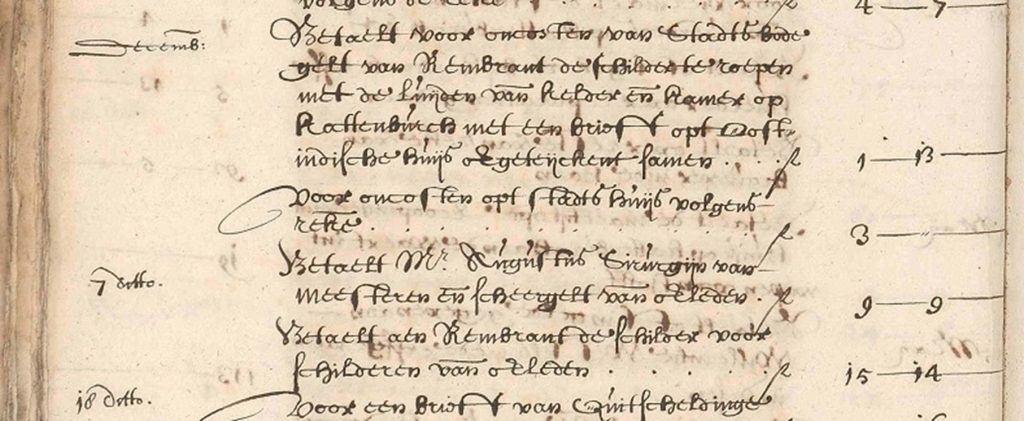

The two hitherto unknown references to Rembrandt were found by the computer in the settlement of the estate of master carpenter Jacob Wesselsz Wiltingh, who died in 1661. In the account of the management of the estate drawn up by the notary Gillis Borsselaer (active in Amsterdam 1636-1675) the expenses and income from the years 1661-1665 are listed in chronological order.5 On 1 December 1663 a payment to the city messenger is noted, relating to three different issues: Rembrandt, the renters of a house in the Grote Kattenburgerstraat and the title of a document (probably a transfer of ownership): “Betaelt voor oncosten van Stadtsbode gelt van Rembrant de schilder te roepen met de luijden vande kelder ende kamer op kattenburch met een brieff opt Oostindische huijs overgeteijckent samen f. 1:13:- (Expenses paid to the city messenger to summon Rembrandt the painter, with the persons in the cellar and the room in the Grote Kattenburgerstraat with a document at the Oost-Indisch Huis transferred total f. 1:13:-)”. The city messenger brought Rembrandt the notice that he was to appear, and the expense post of 7 December 1663 reveals why: “Betaelt aen Rembrant de schilder voor schilderen vande overleden f. 15:14:- (Paid to Rembrandt the painter for painting the deceased f. 15:14:-)”(fig. 4).

Seeing as how the deceased Jacob Wesselsz Wiltingh had already been dead for two years by then, there are three possibilities. The first is that the costs were incurred shortly after the death of Wiltingh and were paid only later. The administrators indeed regularly settled outstanding accounts. Rembrandt could have gone to Wiltingh’s house after the notification from the city messenger in order to make a deathbed portrait there. That would be highly exceptional in Rembrandt’s oeuvre and the price of fifteen guilders and fourteen stivers is strikingly low. And given that all costs after Wiltingh’s death were scrupulously recorded, and no further payments to Rembrandt appear, this is the total amount. Moreover one would not expect the city messenger to be engaged for such a request. The city messengers communicated notifications in the judicial sphere and maintained corresponding registers.6 The settlement of the estate contains other examples. In the autumn of 1662 a city messenger delivered an arrest and twice visited “Els inde kelder op kattenburch (Els in the cellar on the Kattenburch)”, a renter who apparently refused to pay and subsequently went bankrupt, whereupon the estate also had to cover the costs of cleaning up her cellar.7

A second possibility is more likely, namely that Wiltingh was portrayed by Rembrandt already before he died, and that that there was still an amount owing for this that had to be settled in a formal way – therefore the engagement of the city messenger. Despite the fact that the word “remaining” is missing in the text, which indicates in several other estate entries that partial payment had already been made, nonetheless we think that fifteen guilders and fourteen stivers was too modest a sum of money for a portrait painted by Rembrandt. It is more likely that Wiltingh had already advanced a much more substantial sum. A known example of a similar arrangement is the advance of seventy-five guilders that Diego d’Andrada paid Rembrandt in 1654 for the portrait of “seeckere jonge dochter (a certain young woman)”. D’Andrada would pay the balance when the portrait “volcomentlyck sal sijn opgemaeckt (will be fully completed)”.8 And lastly there is still a third possibility, namely that Rembrandt would have made a copy after an existing portrait. Even then the amount is strikingly low and the question arises what the function would be of such a doublet. The East-Netherlandish migrant family to which Wiltingh belonged would not have had a tradition of family portraits, and the idea that a copy would have been destined for one of Wiltingh’s heirs is still quite speculative. And also in such an instance the use of the city messenger would have been very odd.

A third reference to a painter in the estate probably does not have to do with Rembrandt; at least, there is no evidence for this. On 1 June 1662 one of the executors of the estate, Coop Roelofsz Hoijer, received 96 and 12 stivers voor payments he had previously made: ‘Betaelt aen Coophoeijer soo wegen de schilder, Isercramer ende f. 70 vant scheepspart als anders dat den boedel aen hem schuldich was volgens contract f. 96:-:12 (Paid to Coop Hoijer on account of the painter, ironmonger and f. 70 of the share in a ship and for other things that the estate was owing him according to the contract f. 96:-:12)’.9 This payment probably had to do with construction of houses in the Grote Kattenburgerstraat, for which payments to construction workers formed an important part of the settlement of the estate.

It is lastly very likely that the references to Rembrant de schilder do indeed concern Rembrandt van Rijn, and not an unknown painter with the same name. In 1665 Rembrandt had already been a famous artist for decades, who deliberately signed his work “Rembrandt” from the 1630s onwards. In ten Amsterdam estate inventories from the period 1660-1663, in which one or more works by Rembrandt appear, he is only mentioned once with his full name.10 Moreover, Rembrandt as a given name was relatively rare. For the period 1650-1670 the Amsterdam marriage registers list only two adults with the same first name: in 1654 the inland mariner Rembrant Gerritsz van Uithoorn and in 1669 the herbalist Rembrandt Lubbertse.11 That Rembrandt took receipt of the money does not necessarily mean, by the way, that the portrait was painted by him. It could in theory have been carried out by someone from his atelier. From this period, besides his son Titus, only Arent de Gelder (1645-1727) and Gottfried Kneller (1646-1723) have been named as his pupil or assistant.

Who was Jacob Wesselsz Wiltingh?

Rembrandts Amsterdam clientele has been thoroughly researched; it mostly drew from the well-to-do citizens of the city. How do we place master carpenter Jacob Wesselsz Wiltingh in this picture, who was he? The settlement of his estate forms an important source for addressing this question, supplemented by other archival data. The resulting picture is not yet complete, but gives a fairly good impression of his activities and of his close relatives. Jacob Wesselsz Wiltingh (before c. 1630-1661) first surfaces in the Amsterdam documents when he purchases citizenship (poorterschap) on 20 January 1651 as carpenter.12 He was likely unmarried and without children, at least there are no references to be found in the Amsterdam archives and he left no descendants when he died.13 His date of birth is unknow, but he will have been of adult age and he had some capital at his disposal; purchasing citizenship was expensive: fifty guilders. The registration specifies his home town as Hasselt, very likely the small city on the Zwarte Water north of Zwolle.14 Only citizens could become members of the carpenter’s or St. Joseph’s Guild and thereupon undergo a master’s examination, which would allow them to run a business on their own. It is uncertain when he became a master given that the guild archive for this period has been lost. A possible early reference dates to 17 January 1653, when one Jacob Wessels serves as guarantor for the purchase of a building lot on the east side of the Singel by Romeyn de Hoogh, a second cousin of the artist and troublemaker. 15 Starting only in 1655 do we have data available concerning Wiltingh’s activity in two fields, as a commissioned carpenter and as an entrepreneur. He participated in two building projects by city architect Daniel Stalpaert (1615-1676) and he was active as project developer.

18 May 1661 the executors booked the following income entry: “De heeren van Sgraven lant waeren schuldich ende hebben betaelt van timmeren vande kerck aldaer f. 590:-:- (The Lords of ’s-Gravenland were indebted and have paid for carpentry work on the church there f. 590:-:-)”. The church of ’s-Graveland was built in 1657-1658 on the design of Daniel Stalpaert en he will also have coordinated the construction (fig. 5). Wiltingh had contracted on 5 March 1657 for building the roof for a sum of 2050 guilders. This included the roof structure, the tower and the panelling of the ceiling vaults. He took over the costs of the wood, as well as labour costs and beer for the woodworkers.16 He may have undertaken other carpentry work as well. A general account of the building costs mentions that “de kap ende Ander hout werck heeft gemaeckt Jacob van haasselt meester tuijmmerman tot Amsterdam die tselvige werck hadde aen genoemen (The roof and other carpentry work were done by Jacob van Hasselt master carpenter of Amsterdam who had contract to do this work)”. The construction of the church – excluding the foundations – had been estimated to cost between 10,000 and 11,000 guilders, and another source cites a total amount of 12,345 guilders.17

Daniel Stalpaert was also responsible for the supervision of the construction of the Amsterdam City Hall on Dam Square .18 Although this prestige project was one of the most important architectural designs and building projects of the seventeenth century Dutch Republic, our knowledge of the building-process is limited.19 One thing is clear: the sheer size of the project outstripped the capacity of the city construction office, and much work was subcontracted. Untill now hardly anything was known about the carpenters involved in the construction of the City Hall. It turns out that master carpenter Wiltingh was one of the carpenters working in the construction of the roof of the City Hall, together with master carpenter Dirck Isacqsz. Concerning the construction costs a dispute had arisen, that was set aside on Wiltingh’s initiative when Isacqsz visited him at his sickbed and he did not have much longer to live. Wiltingh said: “Meester Dirck wij hebben wat differentie wegen de kap vant stadts huijs, van ontfanck ende uijtgift, maer t is weijnich, ick salder niet lange wesen, laeten wij malcanderen quitteren ende daer van swijgen’ (“Master Dirck we had our differences concerning the roof of the City Hall, income and expenses, but it is little, I do not have long to live, let’s wipe the slate clean and let that be the end of it.”). Whereupon Isacqsz responded “laet het soo doot ende te niet wesen, ende sullen daer van niet meer sprecken off pretenderen” (So let it be finished and undone, and let’s not talk about it or make claims any more.).20 The roof was completed in 1659. According to a description of the City Hall of 1808, construction was contracted to three builders, each earning 6,000 guilders.21 Their names are unfortunately not known, so it is impossible to determine the role of neither Isacqsz nor Wiltingh more specifically.

In 1650 Amsterdam was an important European trading metropolis with more than 170,000 residents, and Jacob Wesselsz Wiltingh was one of the many migrants who gravitated towards the growing city on Amstel. Already starting in 1652, plans were being made for the further expansion of the city, and in order to accommodate the steadily growing population plots within the city were repurposed and existing houses were expanded or rebuilt. Carpenter and bricklayers functioned herein as project developers. They bought existing houses and building plots and the new houses were then sold or rented out.22 Wiltingh worked together with others as project developer, likely to spread out the risk and because his financial means were otherwise insufficient. On 1 February 1655 he bought together with the baker Coop Roelofsz Hoijer (1617/18-1664), probably his brother-in-law, a house in the Jonkerstraat (no. 43 in 1875) for 1017 guilders.23 In the verpondingsregister, a tax on real estate, it is noted that construction work began in 1659. On 1 October 1661 the estimated annual rental income, the basis for the real estate tax, was raised from 50 to 120 guilders.24 The house, “daer eertijts de hoop ende nu de schilpat uijthangt” (“formerly with the sign of Hope, now of The Turtle”).was then worth 3600 guilders.25 This was undoubtedly a new house, although modest in size, and not to be compared to the buildings on the main streets and canals. The lots were small and the Jonker- and Ridderstraat suffered the reputation of being a crowded neighbourhood where unschooled workers, foreigners and sailors stayed, and harboured many prostitutes and cheap bordellos.26 For comparison: the Rembrandt House was sold in 1658 for 11,000 guilders and its rental income was pegged at 350 guilders in the real estate tax register.27

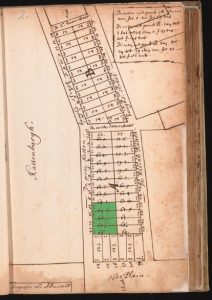

A second building project, about which we know a great deal thanks to the estate documents, comprised of new houses on the newly-formed island Kattenburg. Together with the city master-bricklayer Jan Willemsz Brederode (1621-1671; in city service 1659-1671)28 Wiltingh purchased for 5159 guilders four building lots in the Grote Kattenburgerstraat, on which they built five houses, equally modest in scale (in 1875 nos. 6-14, fig. 6-7).29 Wiltingh knew Brederode from the building of the church in ’s-Graveland, where he had carried out the bricklaying.30 Wiltingh furthermore stood as guarantor, together with Brederode, for the purchase of a building lot in the Kleine Kattenburgerstraat by Dirck Isaacsz, the master carpenter Wiltingh again knew from the roof on the City Hall.31 The properties on Kattenburch island were the first available lots in the fourth expansion of the city, mainly carried out from 1658-1681. They were auctioned on 7 January 1660 and the new houses were completed in the same year.32 On 10 May 1661 Wiltingh and Brederode split up the new building block: Brederode took three houses (nos. 6-10) and Wiltingh two (nos. 12-14), of which one was sold to Roeloff van Aelst (no. 12).33 The estate settlement contains many entries starting in August 1661 for house rent paid by a baker and a tobacconist, and by the residents of an inhabited cellar and front and rear rooms higher up. There are also numerous payments to excavators, pile drivers, wood sellers, bricklayers and other construction workers. When Wiltingh died in May 1661 all of the accounts had evidently not been settled. Furthermore there were unforeseen expenses because the island settled into the IJ. The houses sank, making extra pile driving necessary, and the street had to be raised with sand and “potaert” (clay).34

Settlement of the Estate

Wiltingh died after a period of illness and was buried on 17 May 1661 in a rented grave in the Nieuwe Kerk.35 It is clear from the estate accounts that he received a well-appointed funeral,with food and drinks for the guests afterward. The registration of the burial lists his address as on the Rouaanse Kaai (fig. 8), the east side of the Singel canal between the Korsjespoortsteeg and the Brouwersgracht, a house he had rented.36 The city government tried in the seventeenth century to upgrade the Singel to the fourth main canal by bestowing on it the name of Koningsgracht (“Kings Canal”).37 This renaming did not prove to be an enduring succes, but as a wide residential canal situated between the upscale Herengracht canal and the old centre, the Singel certainly belonged among the city’s better neighbourhoods. Wiltinghs testament, which was drawn up on 10 May 1661 by notary Gerrit Steeman, has unfortunately been lost. In this last will Wiltingh probably had assigned his movable property and at the same time named two estate executors: his (likely) brothers-in-law Jan Roelofsz Boldingh (1617/18-after 1674) and Coop Roelofsz Hoijer (1617/18-1664).38

The latter was previously involved in the construction project on the Jonkerstraat. Both men settled the remaining open accounts and saw to it that the two heirs received their share, as far as the estate, encumbered with debts, allowed.39 Wiltinghs sister Willemtie Wessels received an advance inheritance of 1000 guilders.40 The other heir was Jan Hendricxen Wiltingh (1642/43-after 1664), of whom Boldingh and Hoijer were appointed guardian in Wiltinghs testament41 ;from the documents it is clear that they were close relatives42 . In 1661 Jan Hendricxen resided at Wiltinghs home on the Singel. Upon Wiltingh’s death, Jan Roelofsz Boldingh took care of Jan Henricxen Wiltingh. For the latter the estate did not leave very much. On 16 August 1665 he departed as 22-year-old sailor aboard the VOC-ship Cecilia for the East,43 and nothing further is known about his fate. After his departure followed in October 1666 another settlement of the estate and after this the documents fall silent. A last act dates from 1701 when Debora Bolding, daughter of Jan Roelofsz Boldingh, sold the house on the Grote Kattenburgerstraat (no.14).44

A Possible Identification: the Man with Arms Akimbo

From the above it is clear that Jacob Wesselsz Wiltingh took on major building projects, such as the roof of the church in ’s-Graveland. Besides this he also built on his own account. His contacts with the city construction office were not limited merely to taking on contracts; with the master-bricklayer Jan Willemsz Brederode he worked together on a building project on Kattenburg. Wiltingh lived in a respectable neighbourhood in the city and his grave was in one of the two main churches in the city. He can therefore be positioned in the urban middle class, in the milieu of independent tradesmen and contractors. Gary Schwartz has already indicated that part of Rembrandt’s portrait clientele came from this socioeconomic group, just like Rembrandt himself, by the way.45 A familiar example is Catharina Hooghsaet, who lived in the Haarlemmerstraat as an independent woman and was painted by Rembrandt in 1657.46

But what happened to the portrait of Wiltingh? The settlement of the estate is essentially a bookkeeping, and it shows that the painting was not sold in the years 1661-1666 to benefit the estate. The testament of Wiltingh that notary Gerrit Steeman drew up on 10 May 1661 has unfortunately been lost in the fire that raged in the protocol chamber of the City Hall on the night of 12 to 13 October 1762. It is likely that Wiltingh’s moveable goods including the painting, were already assigned in the testament, because it is striking that the settlement of the estate does not refer to an inventory of the house of the deceased. The advance inheritance issued to his sister Willemtie will also have been mentioned in the testament, and perhaps the portrait came into her possession. Future research into Wiltingh’s family will hopefully yield further information.

Another remaining question is: what did the portrait look like? Within the oeuvre demarcated by the Rembrandt Research Project there is only one possible candidate: an unidentified male portrait from 1658 (fig. 9). The provenance of this painting goes back to 1798, when it was auctioned off with the collection of the Liverpool collector and Rembrandt connoisseur Daniel Daulby (d. 1797); previous collections are not known.47 The dress of the sitter does not correspond to the usual costume of affluent urban Dutchmen of the period. The explanation for this is usually sought in his possible origins in Southern Europe or in his occupation as seafarer.48 But there is no reason to identify him as mariner or even a naval hero, as has been done in the past, since the portrait lacks any nautical or military attributes.49 What the painting does show, is a self-assured man, and even though his clothes and beret are old fashioned, the pose strongly reminds of Rembrandt’s Selfportrait in Working Dress of 1652 (fig. 10). Like Rembrandt, Jacob Wesselsz Wiltingh came from outside Amsterdam, and it is plausible that he looked to emphasize his status as a successful self-made craftsman with a striking, self-confident pose.

- S.A.C. Dudok van Heel, Dossier Rembrandt. Documenten, tekeningen en prenten, Amsterdam 1987, pp. 4-5.

- See: https://archief.amsterdam/indexen/.

- In the process of this indexing several hitherto unknown references to (possible) Rembrandt paintings in inventories surfaced, such as for example Rembrandt’s portrait of Cornelis Claesz Anslo and Aaltje Gerrits Schouten, which according to the testament of their granddaughter Teuntje Hartens hung in the front hall on the Nieuwmarkt; Myrthe Bleeker, “Een Rembrandt in het voorhuis”, Alle Amsterdamse Akten, 8 February 2021, https://www.alleamsterdamseakten.nl/artikel/2648/een-rembrandt-in-het-voorhuis/. Source: Stadsarchief Amsterdam (Amsterdam City Archives) (SAA), access no. 5075, Archief van de Notarissen ter Standplaats Amsterdam (Archive of Notaries in Amsterdam), inv.no. 8511, akte 732, 19 December 1732. Jirsi Reinders en Mark Ponte,“Cardinaal van Rembrandt”, Ons Amsterdam 73 (2021), pp. 38-39; https://onsamsterdam.nl/cardinaal-van-rembrandt-van-rijn. See also the Rembrandt Dossier on the same website: https://www.alleamsterdamseakten.nl/tag/299/rembrandt/.

- SAA, “Google door honderdduizenden historische handschriften”, 9 March 2021, https://www.amsterdam.nl/stadsarchief/nieuws/transkribus/ (accessed 20 October 2021). The search platform can be used at https://transkribus.eu/r/amsterdam-city-archives/#/. More information on Transkribus can be found at: https://readcoop.eu/transkribus/?sc=Transkribus.

- SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 1476 (unpaginated) (scans Archiefbank: KLAG03161000143 – KLAG03161000150) (minuutakte) and SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 1492, f. 305r-312r Afschrift (archive copy), both of 7 August 1665. On 22 October 1666 there was a subsequent report on the management of the estate: SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 1493, f. 156v-159r; idem concerning the pre-bequest to Jacob Wesselsz Wiltingh’s sister Willemtie Wessels: SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 1493, f. 154v-156v.

- Jan Wagenaar, Amsterdam in zyne opkomst, aanwas, geschiedenissen, voorregten, koophandel, gebouwen, kerkenstaat, schoolen, schutteryen, gilden en regeeringe, vol. 3, Amsterdam 1768, pp. 499-502. The city messengers registers have not survived.

- SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 1492, f. 310r-v.

- SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 2196, p. 191; Remdoc no. 1654/4: http://remdoc.huygens.knaw.nl/#/document/remdoc/e1661.

- SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 1476, z.f. (scan Archiefbank: KLAG03161000148) (minutes record); SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 1492, f. 309v Afschrift (archive copy), both 7 August 1665. In the minutes there is a comma between “schilder” (painter) and “Isercramer” (ironmonger), which is missing in the archive copy.

- Estate inventory of Koert Kooper; Remdoc (see note 8) no. 1660/4: Maerten Daey (1660/8), Clara de Valaer (1660/15), Magdalena van Lemens (Remdoc 1661/4), Christoffel Hirschvogel (1661/10), Willem van Campen (1661/11), Willem Schrijver (1661/14), Matthijs Hals (1662/1), Johanna de Smit (1662/1a), Gerard van der Voorde (1663/8). Only in the inventory of Clara de Valaer is the painter named as “Rembrant van Rhyn”.

- SAA, access no. 5001, Archief van de Burgerlijke Stand: doop-, trouw- en begraafboeken van Amsterdam (baptism, marriage and burial books of Amsterdam) (retroacta of the citizen’s registry), inv. no. 473, p. 471; inv. no. 493, p. 120. On 12 November 1654, a child of Rembrandt Gerdes was baptized in the Noorderkerk, inv. no. 76, p. 18. On 19 July 1664, Rembrant van Ruijnen was buried together with his child in the St. Anthoniskerkhof, inv. no. 1193, p. 98.

- SAA, access no. 5033, Archief van de Burgemeesters (Burgomasters’ archive): poorterboeken (citizenship books), inv. no. 2, Register van gekochte poorters (Registry of citizens by purchase), p. 474. Wiltingh is not mentioned in the incomplete surviving registration of baptisms of Hasselt in the years 1591-1597, 1614-1618 and 1632-1651; Historisch Centrum Overijssel, access no. 124 Doop-, trouw- en begraafboeken (dtb, retroacta van de Burgerlijke Stand) in Overijssel (Baptism, marriage and burial books (dtb, retroacts of the civil registry) in Overijssel), inv.nr. 247, Doopboek Hasselt (baptism book Hasselt) 1591-1689.

- This is also evident from his listing in the registers of the collateral succession: SAA, access no. 5046, Archief van de Secretaris: stukken betreffende de ontvangst van de twintigste penning op de Collaterale Successie, inv. no. 2, f. 5v (scan 85). (Archive of the City Secretary; records concerning the collection of the twentieth penny on the indirect inheritance)

- Considering the (familial) relations, this provenance is likelier than from the city of Hasselt in todays Belgian province of Limburg.

- SAA, access no. 5039, Thesaurieren Ordinaris (Treasurers Extraordinary), inv. no. 554, f. 272v. The purchase price was 5600 guilders. In this registry of plots sold by the city during the period 1630-1658 this is the only reference to one Jacob Wessels. The purchases of the lot was Romeyn de Hooghe III (1605-1669), and his brother Daniel de Hooghe (1614-1657) was the second guarantor. On these members of the De Hooghe family: Henk van Nierop, The life of Romeyn de Hooghe 1645-1708. Prints, Pamphlets, and Politics in the Dutch Golden Age, Amsterdam Studies in the Dutch Golden Age, Amsterdam 2018, Genealogical Table 1-2, p. 42 and pp. 420-421.

- Nationaal Archief (National Archives), access no. 3.19.41, Collected papers, from the Van Reede van Oudtshoorn Family, 1321-1902, inv. no. 152, Stukken betreffende den bouw van een kerk, schoolhuis en pastorie te Oudshoorn. 1662-1672, Memoerie vande Oncosten vande kerck van Sgravenlant, with an itemized list of the wooden components of the roof, c. 1659. Meta Döbken, “De ontstaansgeschiedenis”, De kerk te Oudshoorn, Alphen aan den Rijn 1980, pp. 7-19: 16, refered to the existence of this document but did not specify any details.

- See note 16:, Memorie vande Oncoosten…”, c. 1659.

- Pieter Vlaardingerbroek, “De stadsarchitect Daniel Stalpaert (1648-1676): ontwerper of projectmanager?”, Maandblad Amstelodamum 97 (2010), p. 53-61; Gea van Essen, “Daniel Stalpaert (1615-1676) stadsarchitect van Amsterdam en de Amsterdamse stadsfabriek in de periode 1647 tot 1676”, Bulletin KNOB 99 (2000), pp. 101-120; Gea van Essen, Het stadsfabriekambt. De organisatie van de publieke werken in de noordelijke Nederlanden in de zeventiende eeuw, Utrecht 2011.

- Pieter Vlaaardingerbroek, Het paleis van de Republiek. Geschiedenis van het stadhuis van Amsterdam, Zwolle 2011, p. 99, 129-135.

- SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 1492, f. 353r-v.

- Vlaardingerbroek, Paleis (see note 19), p. 99, 134. A fine of 600 guilders was payable for missing the delivery date.

- See: Jaap Evert Abrahamse, Heidi Deneweth, Menne Kosian en Erik Schmitz, “Gouden kansen? Vastgoedstrategiën van bouwondernemers in de stadsuitleg van Amsterdam in de Gouden Eeuw”, Bulletin KNOB 114 (2015), pp. 229-257.

- SAA, access no. 5061, Archieven van de Schout en Schepenen, van de Schepenen en van de Subalterne Rechtbanken (Archive of the Sherriff and Aldermen, of the Aldermen and of the Subaltern Courts), inv. no. 2169, f. 69r. The mutual purchase becomes evident from the settlement of the estate: SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 1492, f. 305v. The Jonkerstraat largely disappeared in the renovation of the neighbourhood, by then decrepit, around 1930; Jonkerstraat 43 was demolished in 1930. Transfers of ownership (Eigendomsoverdrachten) for Jonkerstraat 43 (Verponding 1734: Wijk 10, nr. 2725): SAA, access no. 5061, Archieven van de Schout en Schepenen, inv. no. 2169, f. 69r (29-9-1656); SAA, access no. 5066, Archief van de Schepenen: register van willige decreten van het Hof van Holland (registry of all the decrees of the Court of Holland), inv. no. 227, f. 203r-204r (22-7-1669); SAA, access no. 5062, Archief van de schepenen: kwijtscheldingsregisters (real estate sales registers), inv. no. 84, f. 206v-207r (16-10-1710); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 158, f. 11v-12v (11-2-1784).(Treasurers Extraordinary)

- SAA, access no. 5044, Archief van de Thesaurieren Extraordinaris, inv. no. 282, f. 17r.

- SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 1492, f. 305v.

- Lotte van de Pol, Het Amsterdamse hoerdom. Prostitutie in de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw, Amsterdam 1996, pp. 96-98.

- SAA, access no. 5061, Archieven van de Schout en Schepenen, inv. no. 2120, f. 155v (RemDoc 1658/3); SAA, access no. 5044, Thesaurieren Extraordinaris (Treasurers Extraordinary), inv. no. 281, f. 154r.

- Van Essen 2000 (see note 18), p. 115, Van Essen 2011 (see note 18) pp. 43-44.

- Auction: SAA, access no. 5039, Archief van de Thesaurieren Ordinaris (Treasurers Extraordinary), inv. no. 555, f. 6r-7v (lots A10-A13). Houses: SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 1492, f. 305r. The Grote Kattenburgerstraat disappeared during the city renewal of the 1960s. The houses nos. 8-10 were demolished in November 1945, no. 14 in January 1950 and no. 6 in February 1966. Transfers of ownership Grote Kattenburgerstraat 6 (Verponding 1734: Wijk (District) 16, no. 350): SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters (real estate sales registers), inv. no. 51, f. 141r (16-6-1661); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 55, f. 67v-68v (11-10-1667); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 128, f. 123v-124r (18-7-1754); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 171, f. 263v (15-12-1797); SAA, access no. 5061, Archieven van de Schout en Schepenen, inv. no. 2181, f. 123v (24-1-1810). Transfers of ownership Grote Kattenburgerstraat 8 (Verponding 1734: Wijk 16, nr. 349): SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 51, f. 141v (16-6-1661); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 53, f. 135v (2-11-1661); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 151, f. 144v-145v (28-10-1777); Eigendomsoverdrachten Grote Kattenburgerstraat 10 (Verponding 1734: Wijk 16, nr. 348): SAA, access no. 5061, Archieven van de Schout en Schepenen, inv. no. 2172, f. 244r (24-7-1685); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 65, f. 20v-21r (12-3-1687); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 84, f. 265r (16-5-1710); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 106, f. 1r-v (8-1-1732); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 147, f. 26r-27r (30-6-1773); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 170, f. 289v (25-10-1796). Transfers of ownership Grote Kattenburgerstraat 12 (Verponding 1734: Wijk 16, nr. 347): SAA, access no. 5067, Archief van de Schepenen: register van afschrijvingen bij de willige decreten, inv. no. 23, f. 170r (1-4-1678); SAA, access no. 5066, willige decreten Hof van Holland, inv. no. 34, f. 191r-192v (1-4-1678); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 74, f. 101v (27-8-1700); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 93, f. 141r-v (28-4-1719); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 98, f. 341v (9-11-1724); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 112, f. 3v (28-1-1738); SAA, 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 134, f. 254v-255r (27-8-1760); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 163, f. 372v-373 r (17-7-1798). Transfers of Ownership Grote Kattenburgerstraat 14 (Verponding 1734: Wijk 16, nr. 346): SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 75, f. 135r-136r (11-5-1701); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 102, f. 381r-v (8-10-1728); SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters, inv. no. 198, f. 301r-304r (20-11-1810).

- Döbken, Ontstaansgeschiedenis (see note 16), pp. 7-19: 16; Van Reede van Oudtshoorn papers (see note 16).

- SAA, access no. 5039, Thesaurieren Ordinaris (Treasurers Ordinary), inv. no. 555, f. 14r (lot A 26).

- SAA, access no. 5044, Thesaurieren Extraordinaris (Treasurers Extraordinary), inv. no. 226, pp. 325-326. On 6-12-1660 one of the houses was rented out; SAA access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 3069, f. 276v-277r.

- SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 1492, f. 305r.

- SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 1492, f. 309v, 310v en 311v.

- SAA, access no. 5001, doop-, trouw- en begraafboeken (baptism, marriage and burial books), inv. no. 1055, blad f. 125v.

- In the Verpondingsregister (tax on real estate) of 1659-1661 he is not mentioned as owner, SAA, access no. 5044, Thesaurieren Extraordinaris (Treasurers Extraordinary), inv. no. 282, f. 209v-210.

- Jaap Evert Abrahamse, De grote uitleg van Amsterdam. Stadsontwikkeling in de zeventiende eeuw, Bussum 2010, pp. 236-237.

- Marriage banns of Coop Roeloffss [Hoijer] of Dwingeloo, baker’s apprentice, living in the Dirk van Hasseltssteeg, 29 years old, and Trijntje Jans of Solingen, SAA, access no. 5001, doop-, trouw- en begraafboeken (baptism, marriage and burial books), inv. no. 464, p. 307 (23 March 1647); Hoijer was buried on 10 July 1664 together with his niece or close relative Annetje Roelofs, residing in the house “op de cuijp” by the Engelsesteeg; SAA, access no. 5001, doop-, trouw- en begraafboeken (baptism, marriage and burial books), inv. no. 1055, f. 151v. Marriage banns of Jan Roeloffs [Boldingh] of Dwingeloo, baker’s apprentice, 32 years old, living in the Dirk van Hasseltssteeg, and Marrittie Abrahams, SAA, access no. 5001, doop-, trouw- en begraafboeken, inv. no. 467, p. 464 (19 February 1650). Boldingh probably acquired citizenship on 28 April 1651 as a baker from Coevorden; SAA, access no. 5033, Archief van de Burgemeesters (Burgomasters’ archive): poorterboeken (citizenship books), inv. no. 2, Register van gekochte poorters (Registry of citizens by purchase), p. 482. He is still mentioned on 7 May 1675; SAA, access no. 5063, Archief van de Schepenen: register van schepenkennissen (Archive of the Alderman, register of debt documents), inv.no. 54, f. 32v.

- In October 1666 it was said of the portion of heir Willemtie Wessels: “But seeing as this estate is burdened with many and large debts, it is uncertainfor Willemtie Wessels, having already spent her advance inheritance, that anything will be left after covering all the debts. (Maer alsoo desen boedel noch met vele en groote schulden belast, en onsecker is, datter voor Willemtie Wessels, haer prelegaet alreede wech hebbende, iet boven de voldoeninge van alle schulden zal overschieten) een; SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 1493, f. 158r. On 1-5-1663 it was said of heir Jan Hendricxen Wiltingh that he “possessed very little means” (“seer weijnich middelen heeft”); SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 1491, p. 578. When he left for East India, he owed Boltingh and his wife the amount of 631 guilders, 3 stivers and 8 pennies; SAA access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv.nr 1492, f. 353v-354r).

- Report: SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 1493, f. 154v-156v.

- As “testamentaire vooghden over de nagelatene erfgenamen van Jacob Wesselsz Wiltingh”, this would imply that also Willemtie Wessels was still a minor in 1661; SAA, access no. 5062, Archief van de Schepenen: kwijtscheldingsregisters (Archive of the Aldermen, real estate sales registers), inv. no. 23, f. 135v.

- On 1 May 1663 both Boldingh and Hoeijer are mentioned as guardians and administrators of their nephew (“neve”) Jan Hendricxen Wiltingh; SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv. no. 1491, p. 578. In his last will of 30 July 1665 Jan Hendricxen Wiltingh appointed his cousin (“neve”) Boldingh as his heir. SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv.nr 1492, f. 352v. Most likely, Jan Hendricxen Wiltingh was a son of a brother of Jacob Wesselsz Wiltingh and a sister of Boldingh en Hoijer, though we should keep in mind that “neve” at the time also referred to other close relatives.

- SAA, access no. 5075, Notarissen (Notaries), inv.nr 1492, f. 352v; Dutch Asiatic Shipping (DAS), voyage 1035.1.

- Debora Bolding was the widow of Johannes Paschen. minister at Dwingeloo; SAA, access no. 5062, kwijtscheldingsregisters (real estate sales registers), inv. no. 75, f. 135r-136r. Her marriage banns in Amsterdam, with Boldingh as a witness: SAA, access no. 5001, doop-, trouw- en begraafboeken (baptism, marriage and burial books), inv. no. 501, p.32 (6 October 1674).

- Gary Schwartz, De grote Rembrandt, Zwolle 2006, pp. 197-213, esp. 207-213.

- H.F. Wijnman, “Rembrandt’s portret van Catrina Hoogsaet”, Uit de kring van Rembrandt en Vondel, Amsterdam 1959, pp. 19-38.

- Peter C. Sutton, Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (Leiden 1606 – 1669 Amsterdam). Portrait of a Man with Arms Akimbo, New York (undated) [2011], pp. 9, 11. For an alternative reading of the dress, as historicizing, see: Jacquelyn Coutré, Rembrandt van Rijn’s Portrait of a Man with Arms Akimbo. Kingston 2016 (pdf: downloadable at: https://agnes.queensu.ca/product/rembrandt-van-rijns-portrait-of-a-man-with-arms-akimbo/).

- Ernst van de Wetering, Rembrandt’s paintings revised. A complete survey, Dordrecht 2017, pp. 646-647, no. 261, Portrait of a Man with Arms Akimbo; Sutton [2011] (see note 46), pp. 4-5.

- Volker Manuth, Marieke de Winkel and Rudie van Leeuwen, Rembrandt: The complete paintings, Cologne 2019, pp. 610, 633.