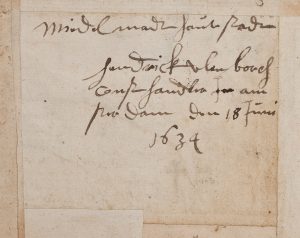

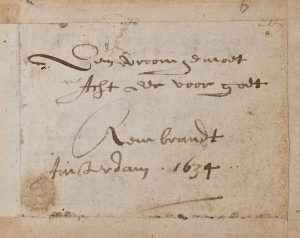

INTRODUCTION Burchard Grossmann the Younger holds a small but honourable place in Rembrandt’s biography as the owner of an album amicorum, or friendship book, in which the artist drew a portrait of an old man that he signed on the facing recto page with the year 1634 (figs. 1, 10).1 For all the familiarity of the drawing, scholarship has done little to clarify its background. Otto Benesch, writing close to sixty years ago, found himself hard put to explain what could have brought Rembrandt and Grossmann together.2 So far as I can tell, only Ben Broos and Gary Schwartz broached the subject to any extent between Benesch and the writing of the present contribution; and despite the efforts of the latter in particular, much remains obscure.3 Indeed, we shall see that closer consideration of Rembrandt’s part in the encounter only deepens the mystery. A chance discovery unrelated to the artist, however, has provided an occasion to find out more about Grossmann – and in so doing, reveal not only a figure of interest in himself but also what could look like the missing link behind the most treasured item in his book.4

Grossmann in fact kept two friendship books; one, started in 1624, stayed mostly with him at his home in Jena or on short trips nearby, while the other, begun in 1629, accompanied him on foreign travels.5 He clearly returned often to both albums as a source of recollection, annotating their pages with information about those who signed them – death dates mostly, but also the dates of events like academic degrees.6 Since 1732, the two albums have formed part of a convoluut, or collective volume, assembled by a functionary at the court of Gera named Paul Andreas Hemmann; in 1896 they entered the impressive collection of alba amicorum at the Royal Library of The Hague.7 Rembrandt’s drawing belongs to the second album; obviously, the library purchased the convoluut precisely for the purpose of obtaining it. Much of our most important information about Grossmann comes from his albums; but a brief account of his life included in the announcement of his funeral by Johannes Zeisold, a professor at Jena and rector of the university at the time of Grossmann’s death, provides some essential framework against which to place the albums’ contents, and a handful of other scattered documents add further elements to the picture.8 GROSSMANN’S LIFE Burchard Grossmann the Younger came from Weimar, in Thuringia.9 His father, a man of wealth and culture, held a court position there from 1603 until 1616, when he became ducal Amtschösser, or tax assessor, in Jena.10 If art historians know the son, historians of music know the father.11 In 1616, the latter experienced a ‘miraculous rescue’ from an unstated but obviously grave calamity; as a sign of thanks, he commissioned no fewer than sixteen settings of Psalm 116 from some of the most distinguished composers in Germany, including Heinrich Schütz, Johann Hermann Schein, and Michael Praetorius.12 The collection, published in 1623 and titled Angst der Hellen und Friede der Seelen, ranks among the most celebrated documents of German sacred music in the early seventeenth century. Zeisold gives the younger Grossmann’s date of birth as 3 October 1605.13 The parents had no other children together.14 Early enrolments at the universities of Leipzig and Jena – the former in summer semester 1612, the latter two summers later – testify to efforts by his father to secure the son’s future.15 Burchard’s actual schooling took place in Weimar, Jena, and, from 1622 to 1623, at the Gymnasium Ruthenicum in Gera.16 In the summer semester of 1624, some months short of his eighteenth birthday, he took the oath that formally admitted him to studies at Leipzig.17 Before Grossmann’s departure from Jena in May 1624, his former tutor Adrian Beyer published a farewell poem, and not a few professors entered inscriptions in his newly initiated album amicorum – a sign, very likely, that he had spent a semester or two of study at Jena before his move.18 Grossmann’s stay in Leipzig – which also included a brief visit to Dresden – lasted until January 1625.19 He remained in Jena the next four years, continuing, according to Zeisold, his studies ‘cum primis Politica’.20 In the spring of 1629, he undertook the first of what would ultimately become three voyages abroad; he obviously began his second album with this journey in mind. His travels over the next twelve months would take him to the northern Netherlands, then to Nuremberg and the neighbouring university town of Altdorf, where he matriculated on 6 April 1630.21 It would seem, however, that Grossmann never completed his studies, but turned instead to military service – to all indications a not uncommon move at the time.22 If inscriptions in his albums before 1630 typically precede his name with adjectives like ‘politissimus’, ‘literatissimus’, or ‘wohlgelahrt’, from early that year and increasingly thereafter we also find the attribute ‘mannhaft’.23 Entries from October 1630 and later describe him as an officer, sometimes more specifically as a ‘Fendrich’, or standard bearer.24 From this point on, not a few writers pay tribute to both sides of his accomplishments with pairings like ‘Artis et Martis cultori’, ‘rei literariae ac militaris’, ‘Tum Palladis tum Bellonae castra’, or, most fulsomely, ‘variae, et exquisitae eruditionis, ut et militaris scientiae, & experientiae’.25 After his return from Nuremberg and Altdorf, Grossmann remained in Jena for another four years.26 In the spring of 1634 he embarked on his second journey – the one that led to Rembrandt’s drawing. This lasted six months, from May to November; we can identify the principal destinations as Amsterdam, The Hague, Frankfurt am Main, and, perhaps, Hamburg.27 The longest stay, in Frankfurt, coincided with the final weeks of the Convent of Frankfurt, with which the Swedish general commander Axel Oxenstierna hoped to unite the Protestant side in the Thirty Years War.28 The possible significance of this will occupy us later. Grossmann travelled abroad for the last time in 1636.29 This journey, lasting from May to October, led via Nuremberg and Regensburg to Vienna, and from there, after a stay of several weeks, through Prague and Dresden back to Jena – from which, however, he departed almost immediately for Leipzig, where he spent almost seven months, to all indications in connection with the defence of the city against a siege instituted by the Swedish general Johan Banér.30 Grossmann’s time in Vienna adds another, if still elusive, wrinkle to his biography: an inscription entered at Schloss Pellendorf, home to a branch of the widely ramified Austrian noble family Herberstein, describes him as ‘Hofmeister’ to Georg Jacob Freiherr zu Herberstein, and both Georg Jacob himself and his uncle Julius Freiherr zu Herberstein contributed dedicatory inscriptions as well.31

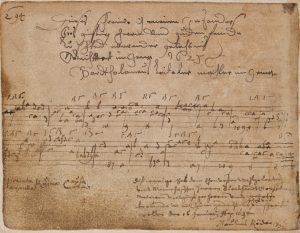

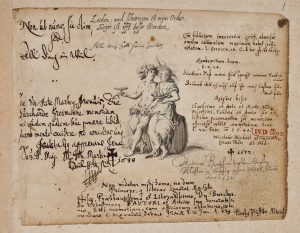

On 27 June 1637, not long after Grossmann’s return from Leipzig, Burchard Grossmann the Elder died.32 Two years later, Grossmann may have resumed his studies at Jena.33 On 16 February 1641, in Gera, he married Maria Glaser, the daughter of an official there.34 Friends and others, including Zeisold and Beyer, contributed to a volume of poems honouring the pair; Grossmann’s father-in-law commemorated the occasion a month later with a suite of four gouaches, the last of which depicts a couple – presumably meant to portray Burchard and Maria – dancing to nearby musicians (fig. 2).35 At the time of the wedding or shortly afterwards, Grossmann moved to Gera.36 According to Zeisold, he and his wife had two children. In this period, perhaps because of his more settled existence, the once steady stream of entries in his albums peters out; it comes to a complete stop in February 1645, a month after Grossmann returned to Jena to seek treatment for a sudden intense illness.37 He did not recover, but died in Jena on 23 March.38 GROSSMANN’S PURSUITS Despite what we learn from documents like Zeisold’s funeral announcement and the matriculation registers, or can deduce from the friendship books, not a little about Grossmann remains obscure. We never hear of a position in either Jena or Gera, and neither the funeral announcement nor that for his father refers to his military service in more than passing terms or mentions his attachment to Georg Jacob zu Herberstein.39 His father seems not to have had a very high opinion of him. When the elder Grossmann wrote his will in 1636, he complained of long having to subsidize his son’s ‘idle life’ to the tune of a thaler per week upkeep and twenty thalers for a horse; accused the son of harbouring unjust resentment toward him; and added that the younger Burchard had ‘pointlessly and uselessly’ squandered an inheritance from his grandmother ‘with traveling, squabbling, and idleness’.40 We shall see that the reference to travel, at least, might not capture the whole story; perhaps we should treat the elder Grossmann’s views with caution, as he does not even spare a word anywhere for his son’s evident military capabilities and exhibits a somewhat crotchety temperament throughout his will. Even allowing for the tendency to flatter, moreover, the dedicatory tributes quoted earlier hardly seem indicative of a ne’er-do-well. Whatever the truth, Grossmann’s albums certainly testify to contacts both with the upper echelons of political authority and with men of learning and the arts.41 When he visited Dresden in October 1636, for example, contributors to his friendship book included the four sons of the elector, the powerful Oberhofprediger Matthias Hoë von Hoënegg, and the court Kapellmeister Heinrich Schütz.42 Schütz, of course, had had dealings with Grossmann’s father, if perhaps only through correspondence. But even apart from this, music would appear to have played a role of some importance in the younger Grossmann’s life.43 His father bequeathed him several volumes of music – including some of particular value – as well as musical instruments. A tablature inscribed on the lower half of a page in the first album amicorum indicates that he played the lute with more than passing skill (fig. 3).44 Three of the composers represented in the Angst der Hellen dedicated puzzle canons to him; a correction in one of these could even indicate that he knew counterpoint sufficiently well to ferret out an error. The albums also contain a further purely verbal inscription by a musician, although in this instance not a famous one.

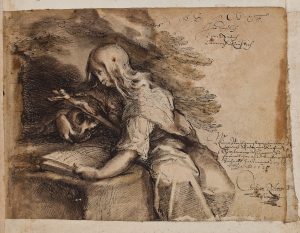

Even more than music, Grossmann’s albums suggest an interest in the visual arts. As Schwartz already observed, ‘many artists … decorated [them] with drawings’; and if the number and concentration of these do not approach, say, the famous collection in the album of Jacob Heyblocq, their very geographical and chronological spread surely indicate that Grossmann made it a point to seek out their makers.45 The album containing the Rembrandt drawing preserves no fewer than eight others by artists who either identify themselves as professionals or whom we can identify with greater or lesser security as such through external evidence or the appearance of their work.46 These include the Leipzig goldsmith August Richter and the otherwise unknown Leipzig painter Johann Deuerling; the Regensburg painter and engraver Jörg Christoph Eimmart (fig. 4); a painter or apprentice – an early restoration has obscured the portion of his inscription that would tell us which – named David Mentzel; a draftsman with the first name Samuel and a hard-to-read surname possibly decipherable as ‘Tewrer’; another unknown, Valltien Kurtz; and two unquestionably capable artists who left their work without any name at all (fig. 5).47

Grossmann’s first album holds an even larger stock of drawings. Artists who contributed to the book in Jena or presumably nearby include Friedrich Wilhelm Franck, Martin Thurschalla, and Andreas Zeideler.48 Nine further items no doubt added locally, although unsigned or by authors neither self-identified nor otherwise documented as artists, also look skilful enough to come from professional hands.49 A visit to Leipzig in 1632 brought drawings by the painter and engraver Andreas Bretschneider and a presumed relative, Hans Daniel Bretschneider.50 Perhaps most important, both the Weimar court painter Christian Richter – no relation to the August of Leipzig – and a young son of the same name make appearances here, as does another member of the family, Jeremias Richter (fig. 6).51 The inscription accompanying the elder Richter’s drawing addresses Grossmann as his ‘Schwager’ – strictly speaking, brother-in-law, although the term can also refer to any relative by marriage, and surely does so here: Grossmann, then only nineteen and still single, had no full siblings, nor have conjugal links between his parents’ immediate families and the Richters yet come to light.52 Nevertheless, just as we can trace Grossmann’s musical inclinations back to his father, it could look as if his interest in the visual arts also had its roots in his family. If the albums offer signs of what we could regard as artistic sympathies, they also undercut a recurrent misconception about Grossmann. More than one writer has seen him as a man of commerce: Julius Held, for instance, called him a ‘merchant’, Schwartz a ‘traveling salesman’, perhaps ‘in the arms business’.53 Given the general reticence of the funeral announcement, some might not wish to lend much weight to the fact that it does not yield any clues in this direction. Yet Hemmann, whose prefatory notes to the two albums leave no doubt that he combed them for biographical information, also fails to describe Burchard Grossmann in terms even suggestive of someone engaged in business.54 Nor has my own examination of the books revealed many contacts suggestive of commercial pursuits. Indeed, apart from Rembrandt’s landlord and agent Hendrick Uylenburgh, I have spotted only one, a Leipzig merchant named Christoph Grossmann; and since he describes himself as a relative, we may well think that family ties, not economic interests, lay behind his meeting with Burchard.55 No less important, I can find none of the adjectives commonly used to characterize Grossmann used elsewhere in conjunction with merchants. This applies particularly to ‘wohlgelahrt’, which plainly carried with it the implication of higher studies. A survey of funeral sermons and wedding tributes published in German-speaking countries from 1600 to 1650 yields not a single instance of a merchant – Handelsmann – described as ‘wolhgelahrt’.56 This should not surprise us: by all indications, men of trade did not attend university but learned through the apprenticeship system.57 Grossmann’s service to one of the Herbersteins, if still obscure, also testifies to a social status distinct from that of a traveling salesman. Obviously, we must reconsider some other impressions about Grossmann that have made their way into the literature. For one thing, we cannot sustain the idea that his voyage to Amsterdam in 1634 had an entrepreneurial motive of any sort.58 It might still, however, have had something to do with armaments, even if not in the terms hitherto proposed. As Schwartz pointed out, Grossmann’s second album includes more than a few signatures of princes involved in the Thirty Years War, as well as that of Joachim van Wicquefort, the agent in the Dutch Republic of Grossmann’s sovereign, the duke of Saxe-Weimar.59 Without exception, these belong to the year 1634; so, too, do several entries by children of rulers enmeshed in the conflict.60 The album also contains a striking number of entries by legates and other participants at the Convent of Frankfurt, which suggest that Grossmann took active part in the day-to-day proceedings of the convent.61 Against this background, we could find it more than coincidental that Amsterdam and Hamburg represented the dominant centres of the arms trade in northern Europe during the Thirty Years War – the Dutch metropolis as ‘above all the central supplier of munitions and weaponry for anti-Habsburg Europe’, while the Hanseatic city had become ‘the northern European centre of information for all the parties in the war, the hub of monetary transactions and of deals, especially those concerning the supply and arming of the military’.62 As an officer from a prosperous and well-connected family, Grossmann could perhaps have sought to facilitate purchases of munitions for a native land deeply immersed in a brutal war.63 Hence despite his father’s withering remarks, his voyage may have entailed matters considerably beyond his own amusement. But we do not know; and whatever the case, in any arms deal he pursued he would have acted not as an independent agent but, surely, on command from higher powers.64 We may look no less sceptically on ‘the possibility’, as Schwartz puts it, that Grossmann ‘traded in art on the side’.65 At the very least, the drawings in his albums cannot have served any immediate material purpose. It seems clear, for one thing, that no one – neither the artists nor Grossmann himself – anticipated their removal. Admittedly, almost all of them lack dedicatory inscriptions, which in principle would have made it easier to detach and sell them.66 Yet not only did artists routinely omit such inscriptions even when contributing to the albums of relatives or close friends, but Martin Thurschalla, one of the draftsmen who accompanied his drawing with nothing more than his name, fit his work into leftover space on a page already written on by someone else (fig. 7).67 Conversely, Johannes Deuerling’s drawing had its page to itself for barely a month before someone surrounded it with a lengthy inscription; the reverse side of the leaf on which August Richter made his drawing remained blank for no more than ten days; and no fewer than three later contributors added inscriptions to the page with Andreas Bretschneider’s drawing (fig. 8).68 Even without such evidence, in fact, one must wonder about the plausibility of viewing drawings in friendship books from anything but the most remote commercial perspective. If an artist wanted to demonstrate his skills for a buyer elsewhere, he could more easily have produced a separate sheet that an intermediary could pass on, rather than something that would remain within the covers of a personal book; if he wished simply to impress a prospective purchaser, a tour of the studio would have sufficed.69

To all indications, Grossmann met artists much as he met anyone else who signed his albums. We get a sense of this, I would suggest, from the context surrounding two of the drawings in the first album amicorum. A series of entries there documents a brief trip to Leipzig in the early summer of 1632. The first entry belongs to Christoph Grossmann, who signed on Monday 25 June; as we have seen, this could well reflect nothing more than a reunion of family members.70 The next day brought contributions from no fewer than five people: three students – one of them a nobleman – and the Bretschneiders.71 On Wednesday two more students signed the album; these included Christian Michael, already known as a composer and soon to become organist at the church of St Nicholas in Leipzig, who inscribed one of the puzzle canons referred to earlier.72 Finally, on Thursday 28 June Hieronymus Reckleben, professor of logic at the university, added his inscription.73 On this visit, in other words, Grossmann appears to have consorted all but exclusively with members of the academic community or creative artists – in the case of Christian Michael, both at once. I would pause a moment longer over the canon that Michael entered the day after the Bretschneiders contributed their drawings. Grossmann cannot have had any pecuniary interest in this little musical exercise, or in any of the music in his albums. He could have invited others to share the challenge of resolving the canons; he could possibly have played the lute piece for interested friends. But music on paper – especially music in a personal book or in the abbreviated notation of canons – did not really exist as fungible currency in that time. Short of perhaps a good report on his talents to possible future employers, Michael, too, had nothing to gain from the little bit of notation with which he graced the album of a former patron’s son.74 I would think that we must see the drawings in essentially the same light: just as they, like the music, sit with no perceptible line of demarcation among entries of more usual sorts, so too do the circumstances of their creation, insofar as we can trace them, fail to hint at anything that would mark them as something other than tokens of social interchange. Let me summarize the picture we now have of Burchard Grossmann the Younger: a wealthy young man, close in age to Rembrandt; literate; well versed in music; and particularly given to the visual arts and conversant – if strictly as a well-born amateur – with those who made it.75 It takes no stretch of the imagination to read this description as that of a very suitable patron for Rembrandt. This, in fact, removes one of the issues that troubled Benesch, who claimed that Grossmann ‘was hardly very interested in art’.76 Yet it does not remove every anomaly. GROSSMANN AND REMBRANDT

Although Rembrandt left his drawing in Grossmann’s second album amicorum undated but for the year, everyone agrees that it must come from June 1634. Indeed, as Broos seems first to have observed, it all but certainly dates from 18 June, as Uylenburgh, in whose house the artist lived and whose cousin Saskia he would marry shortly afterwards in Friesland, made an entry of his own on that day.77 This brings us to the nub of the problem: what led Grossmann to Uylenburgh’s house, and why should Rembrandt favour the German visitor with a drawing? For all of Grossmann’s obvious responsiveness to art, his albums give no indication that he knew any artist in the Netherlands other than Rembrandt. Yet Rembrandt, as Benesch pointed out, did not enjoy more than essentially local – or in any event not very wide-ranging – celebrity in 1634.78 Supposed indications to the contrary dematerialize on closer inspection. The longstanding assumption that Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione in Genoa knew etchings of Rembrandt by that year has no basis.79 Similarly, while the French-texted music in one of Sebastian Stoskopff’s two still lives with reproductions of early Rembrandt etchings could support the assumption that both predate Stoskopff’s return from Paris to his native Strasbourg in or around 1640, the upper end of the dating ‘Vers 1631-1635’ given by one of the principle monographs represents only an approximation.80 The three paintings given by Robert Kerr to Charles I of England between 1629 and 1639 appear not to have brought any others in their wake until the next decade at the earliest; and however credible the speculation that Richelieu’s agent Alfonso Lopez purchased Balaam from Rembrandt in the late 1620s, some ten years before their first documented contact, this transaction, too, had no identifiable successors.81 Etched copies by Wenceslaus Hollar of Rembrandt’s Naked Woman Seated on a Mound and Saskia with Pearls in her Hair, both dated 1635, also leave matters unchanged, as Hollar visited Amsterdam the previous year; not only do we thus have no reason to think he would have become acquainted with these works anywhere else, but we could even read his decision to copy them as an indication that he expected no one in Germany to know the originals first-hand.82 Finally, reproductive etchings associated with Willem de Leeuw that some regard as evidence for knowledge of Rembrandt in Flanders around 1633 originated both at a slightly later date and – more important – in the Dutch Republic.83 Rembrandt’s fame would spread soon enough, of course. But for the early years of the decade, Benesch’s conclusion seems to hold. At first sight, this could appear to support the idea that Grossmann, even if not someone engaged in commerce, came to Uylenburgh looking to make a purchase or commission – either for himself or for another party – and simply chanced on the rising young painter living there.84 It does not take long, however, for second thoughts to emerge. These start with Grossmann himself. To all appearances, his part of the world lacked anything like what we would call an art market.85 Hence, short of assuming that someone else sent him to Uylenburgh, his presence there as a customer presupposes a greater familiarity with how things worked in Amsterdam than we might want to ascribe to him after barely a day or two in the city.86 More crucially, a surprise encounter hardly explains Rembrandt’s side of the equation. As Benesch also noted, the artist did not make a habit of contributing to friendship books.87 We know of only two others that contain drawings of his; and not only do both of these volumes date from many years after Grossmann’s, but one belonged to a friend of long standing, the other to someone with whom Rembrandt would have had more than a few friends, acquaintances, and professional associates in common.88 As our consideration of the other drawings in Grossmann’s albums has shown, Rembrandt would have had nothing obvious to gain through volunteering one of his own; nor can we assume that the book Grossmann gave him to sign offered a precedent for doing so – the dated drawings elsewhere in its pages all come from later years.89 This leaves those who would frame the situation in more or less simple economic terms with three possible scenarios: Grossmann paid for the drawing; Rembrandt received no money but made it to curry favour with a potential source of future income; or he rewarded Grossmann with a bonus for engineering a lucrative arrangement of some sort.90 None of these strikes me as very realistic. All of them, for one thing, would have contravened what we might describe as the ethos of the friendship book: Not even contemporaries who took a dim view of the entire phenomenon claimed that anyone demanded payment for an entry, or that those soliciting one offered any inducement beyond a drink – a point implicitly underscored by Rembrandt himself in the familiar inscription to his drawing, ‘Een vroom gemoet | Acht eer voor goet’.91 The second and third scenarios, meanwhile, presuppose an artist far more accommodating to sources of patronage than shown at least in documents from later in his life. True, his letters to Constantijn Huygens, still in the 1630s, about the Passion paintings commissioned by Frederik Hendrik show him able to play the register of courtly obsequiousness when necessary; but I wonder how much we can infer from that example about his relations with members of other social milieus.92 Nor does Grossmann seem in a position to have advanced Rembrandt’s interests in any particular way – certainly, historians have yet to discover an early concentration of Rembrandt paintings, or even etchings, in Germany that could bolster suspicions in that direction.93

Puzzlement over what stubbornly refuses to look like anything but an uncharacteristic gesture on Rembrandt’s part would vanish, of course, if the artist already knew Grossmann, or if they at least knew someone in common. Curiously, this suggestion seems not to have surfaced anywhere since Benesch, who rather fancifully proposed that Grossmann’s father might have visited Holland at an earlier time.94 Yet a closer look at Grossmann’s first voyage to the Netherlands makes one wonder why not. The earliest dated entries in his second album amicorum document contacts with notable scholars at the University of Leiden: on 8 June 1629 the rector, the philosopher Franco van Burgersdijck, entered an inscription; in the same month, although without a specific date, the philologist and poet Daniel Heinsius did so as well.95 Grossmann had clearly come to Leiden directly from Jena, which he had left less than four and a half weeks earlier; especially if we bear in mind his subsequent matriculation at Altdorf, the presence in his album of two such prominent academics encourages the suspicion that he embarked on his journey with the intent of pursuing studies at Leiden.96 The matriculation records of the university, however, do not show his name, and his album contains no further entries for several months.97 But could this very silence mean that he remained in Leiden, even without matriculating, for a while?98 By all indications, he did not venture very far afield during this period: when the entries in his album resume, in late February 1630, they show him in The Hague and vicinity, then Dordrecht, obviously on his way to Nuremberg.99 It may also speak for prior experience at the university that he seems to have gravitated there when he returned briefly to Leiden in July 1634: of the four entries in his album from those days, one belongs to a professor and two to students from Germany.100 The fact that Grossmann – especially given what we now know of him – passed through Rembrandt’s home town in 1629 and could even have spent some months there has provocative implications. However far the artist’s reputation did or did not extend at the time, art lovers in Leiden had clearly taken notice of him; hence a visitor of Grossmann’s inclinations could scarcely fail to have heard his name.101 But at this point, the gaps in the evidence urge us not to push speculation further. Much as I should like, for instance, to strengthen my inferences about Grossmann’s first stay in the Netherlands by showing that he acquired a working knowledge of Dutch, his album hardly allows for definitive conclusions on the matter: although Rembrandt and Uylenburgh wrote in their native language, the only other entries by Dutchmen not written in Latin either use German or combine a Dutch heading with a German – if rather Dutch-inflected – body text.102 Similarly, while Daniel Heinsius could look like an especially tantalizing figure when we realize that he not only contributed to Grossmann’s album but also had close ties to Rembrandt’s probable early supporter Petrus Scriverius, his potential significance diminishes with the discovery that he turned out inscriptions for visiting German students by the dozen, almost always following the same standard pattern as in the one he wrote for Grossmann: the motto ‘Quantum est quod nescimus’ at the start, a quotation from Theocratus at the end.103 In all likelihood, we shall never know for sure whether Rembrandt and Grossmann met in Leiden.104 Nor can we tell how Grossmann, five years later, would have known of Rembrandt’s move to Amsterdam, although it doesn’t take much effort to come up with plausible hypotheses: mutual contacts, for example, could easily have passed on news of Rembrandt’s whereabouts. Still, I think the probabilities favour the assumption that when Grossmann visited the home of Hendrick Uylenburgh in June 1634, he went there specifically to see Rembrandt – and that he did not come as a stranger. In other words, on present evidence it looks more likely than not that Rembrandt drew his portrait of an old man for someone he knew well enough, whether through first-hand acquaintance or through a trusted recommendation, to consider worthy of such a gift.105

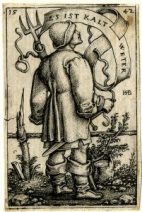

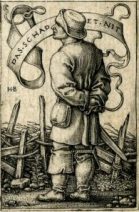

Grossmann’s visit may have left one further trace. Rembrandt’s graphic output includes a curious pair of etchings (fig.11) in which two peasants comment on the weather: ‘Tis vinnich kout’ says the first, to which the second responds, ‘Dats niet’ – ‘It’s awfully cold’; ‘That’s nothing’.106 The images and the inscriptions derive from two much older works by Sebald Beham; there, the texts read ‘ES IST KALT WETER’ and ‘DAS SCHADET NIT’ (fig.12).107 Just as Rembrandt treats Beham’s figures with considerable freedom, his rendering of the peasants’ remarks also takes some liberties with the original, both in the added intensifier ‘vinnich’ and in the compression of ‘das schadet nit’, which literally means ‘that doesn’t do any harm’.108 Whether or not Rembrandt knew any German, his Dutch reads not so much like a translation made directly from a written text as it does like remembered snippets of conversational paraphrase – an impromptu explanation of Beham’s inscriptions.109 The two etchings stand out as anomalies in Rembrandt’s output. Their very identity as a pair renders them singular, as does the presence of spoken vernacular text. Even the subjects, conventional as they may seem, mark the prints as a rarity. At latest count, Rembrandt created only two other etchings devoted to peasants, and none between ca. 1630 and the start of the 1650s; nor does theperiod to which the Beham adaptations belong include more than a very few genre subjects of any sort.110 Attributing all these features to dependence on his model only begs a more fundamental question. Rembrandt did not take anything else from Beham.111 Indeed, he seldom relied on German precedents; and when he did, he typically borrowed nothing more than isolated motifs, only once – and quite a bit later – appropriating more or less a whole composition.112 We might wonder, therefore, what stirred him to make such an unusual adaptation of such a remote source – especially if he needed someone to translate the peasants’ exchange. It could thus seem of more than routine interest that the calling peasants, insofar as we can assume both to have borne the same date, come from the same year as an art-loving German’s visit to Rembrandt in Amsterdam; indeed, statistics favour, if ever so slightly, a dating after Rembrandt and Grossmann met.113 Does it go too far to suspect a connection here?

Certainly, it takes little effort to imagine possibilities. We could think, for example, that Grossmann – whose artistic inclinations would hardly not have extended to prints – presented these tiny keepsakes to Rembrandt; one can even picture the two of them, together with Uylenburgh, contemplating and discussing Beham’s work.114 Those who would rather assume that Rembrandt acquired the two Beham engravings in his normal course of collecting might nevertheless see him bringing them out to ask his guest about their inscriptions; or recollection of the meeting with Grossmann could have prompted him to take what turned into a productive new look at them. Some, of course, may prefer to avoid such speculation entirely and consider Rembrandt’s engagement with Beham a purely internal affair, stimulated by nothing more than his appetite for competition with eminent predecessors; should he have needed help with Beham’s German, this argument might go, Uylenburgh could have provided it – Uylenburgh had lived, after all, for a time in Danzig, a city with a largely German population.115 Yet Danzig also included a sizeable number of Poles, whose language Uylenburgh had evidently learned growing up in Kraków, and a substantial Dutch contingent as well, so we cannot assume too much about his interactions with the German majority.116 In fact, I know of no real evidence that Uylenburgh knew German – if anything, his use of Dutch in Grossmann’s album implies the opposite.117 With Grossmann, on the other hand, all the pieces fit together. Hence even if we cannot prove that he had a part in the story behind Rembrandt’s two peasants, the supposition that he did would clear up yet another small puzzle in the artist’s work. About the author: Joshua Rifkin has performed and recorded extensively as conductor, pianist, and harpsichordist, and pursues research in music (Josquin Desprez, Heinrich Schütz, J. S. Bach) and art (Willem de Leeuw, J. G. van Vliet, Gerbrand van den Eeckhout). Recent publications include ‘Musste Josquin Josquin werden? Zum Problem des Frühwerks’, Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 74 (2017) 162–84; and ‘Milan, Motet Cycles, Josquin: Further Thoughts on a Familiar Topic’, Daniele V. Philippi and Agnese Pavanello (eds.), Motet Cycles between Devotion and Liturgy (Basel 2019) 221-335.

Certainly, it takes little effort to imagine possibilities. We could think, for example, that Grossmann – whose artistic inclinations would hardly not have extended to prints – presented these tiny keepsakes to Rembrandt; one can even picture the two of them, together with Uylenburgh, contemplating and discussing Beham’s work.114 Those who would rather assume that Rembrandt acquired the two Beham engravings in his normal course of collecting might nevertheless see him bringing them out to ask his guest about their inscriptions; or recollection of the meeting with Grossmann could have prompted him to take what turned into a productive new look at them. Some, of course, may prefer to avoid such speculation entirely and consider Rembrandt’s engagement with Beham a purely internal affair, stimulated by nothing more than his appetite for competition with eminent predecessors; should he have needed help with Beham’s German, this argument might go, Uylenburgh could have provided it – Uylenburgh had lived, after all, for a time in Danzig, a city with a largely German population.115 Yet Danzig also included a sizeable number of Poles, whose language Uylenburgh had evidently learned growing up in Kraków, and a substantial Dutch contingent as well, so we cannot assume too much about his interactions with the German majority.116 In fact, I know of no real evidence that Uylenburgh knew German – if anything, his use of Dutch in Grossmann’s album implies the opposite.117 With Grossmann, on the other hand, all the pieces fit together. Hence even if we cannot prove that he had a part in the story behind Rembrandt’s two peasants, the supposition that he did would clear up yet another small puzzle in the artist’s work. About the author: Joshua Rifkin has performed and recorded extensively as conductor, pianist, and harpsichordist, and pursues research in music (Josquin Desprez, Heinrich Schütz, J. S. Bach) and art (Willem de Leeuw, J. G. van Vliet, Gerbrand van den Eeckhout). Recent publications include ‘Musste Josquin Josquin werden? Zum Problem des Frühwerks’, Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 74 (2017) 162–84; and ‘Milan, Motet Cycles, Josquin: Further Thoughts on a Familiar Topic’, Daniele V. Philippi and Agnese Pavanello (eds.), Motet Cycles between Devotion and Liturgy (Basel 2019) 221-335.

This essay, although written and scheduled for publication some ten years ago, fell victim to circumstances that delayed its appearance until now. I owe its inclusion in the present Kroniek to David de Witt and Michael Zell, as well as to support of various kinds from Judith Noorman and Jeroen Vandommele. Both the character of the text itself as well as external factors have precluded any but minor revisions – although fortunately, nothing in the subsequent literature has demanded more. I should draw special attention, however, to Judith Noorman’s independent, if necessarily abbreviated, treatment of the same subject cited in note 1 below, and also to the article of Stephanie Sailer cited in note 88 below; my thanks, too, to David de Witt for his careful, and often productively sceptical, reading of what follows. Going back further in time, I continue to owe warmest thanks to the two dedicatees for information and encouragement, and to Michael Zell, who also encouraged my research in its initial stages and offered several helpful suggestions.

- See, fundamentally, O. Benesch, The Drawings of Rembrandt, 2nd ed., rev. E. Benesch, 6 vols., London 1973, vol. 2, p. 67, no. 257; M. Royalton-Kisch and P. Schatborn, ‘The Core Group of Rembrandt Drawings, II: The List’, Master Drawings 49 (2011), pp. 323-346, at pp. 329-330, no. 20; M. Royalton-Kisch, The Drawings Of Rembrandt: A Revision of Otto Benesch’s Catalogue Raisonné, 2012- (http://rembrandtcatalogue.net/, accessed 10 January 2021), Catalogue, under Benesch 0257; and W. L. Strauss and M. van der Meulen, The Rembrandt Documents, New York 1979, p. 111, no. 1634/6. For the original see The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, 133 C 14 – C (Album amicorum II), fol. 233.5v-233.6r. J. Noorman ‘Rembrandt in Friendship Books’, in Rembrandt’s Social Network. Family, Friends and Acquaintances, exh. cat. Amsterdam (Museum Het Rembrandthuis) 2019, pp. 104–109, at pp. 104–105 and 107, writes mistakenly that the inscription appears on the verso of the drawing: Rembrandt, as Jeroen Vandommele helped me confirm, entered the drawing on the verso of a leaf already inscribed on the recto in 1630 (fol. 233.5r; see note 21 below), the signature on the recto of a leaf still blank on both sides, although not for long (fol. 233.6v; see notes 7 and 27 below). The spelling of Grossmann’s given name follows autograph examples on fol. 94r and 211.1r of the same source; German-language scholars referring to him or his father more often use ‘Burckhard’. Both Grossmanns spell the family name sometimes with, sometimes without, the doubled s – written by them as ß – or n.

- See O. Benesch, ‘Schütz und Rembrandt’, in W. Gerstenberg, J. LaRue, and W. Rehm (eds.), Festschrift Otto Erich Deutsch zum 80. Geburtstag am 5. September 1963, Kassel 1963, pp. 12-19, at pp. 18-19; in English as ‘Schütz and Rembrandt’ in Benesch, Collected Writings, ed. E. Benesch, 4 vols., London 1970-1973, vol. 1, Rembrandt, pp. 228-234, at pp. 233-234.

- See B. P. J. Broos, review of Strauss and Van der Meulen 1979 (note 1), Simiolus 12 (1981-1982), pp. 245-262, at pp. 252 and 254; and G. Schwartz, Rembrandt. His Life, His Paintings, New York 1986, pp. 186-188 and 369.

- For the earlier discovery see J. Rifkin, ‘Heinrich Schütz und seine Brüder: Neue Stammbucheinträge’, Schütz-Jahrbuch 33 (2011), pp. 151-167, esp. pp. 166–167. Readers consulting that article – portions of which inevitably overlap with this one – should observe that footnotes in the present text cited there (see pp. 163-165, notes 54, 58, 60, and 69) no longer have the same numbers: references to notes 20, 25, and 32 should now read one number higher, that to note 59 should read 61.

- Cf. Schwartz 1986 (note 3), p. 187, and the further discussion below. On the practice of keeping more than one album see W. W. Schnabel, Das Stammbuch. Konstitution und Geschichte einer textsortenbezogenen Sammelform bis ins erste Drittel des 18. Jahrhunderts (Frühe Neuzeit 78), Tübingen 2003, pp. 142-143.

- See, for instance, notes 48 and 50 below; also Schnabel 2003 (note 5), pp. 163-164.

- I draw this and much of the other information to follow from the online catalogue of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek (http://opc4.kb.nl/DB=1/SET=2/TTL=1/SHW?FRST=3), which provides colour scans of every entry in both albums; see also Kunstantiquariat Samuel Kende, Katalog der reichhaltigen Sammlungen weiland Sr. Excellenz des Herrn Grafen Ludwig Paar, Vienna 1896, pp. 60-61. The convoluut as a whole bears the call number 133 C 14, with Album amicorum I given the sub-designation B, Album amicorum II C. In their original state, the albums consisted, respectively, of 228 and 144 leaves, many of which still bear their original foliation, apparently in Grossmann’s hand; their remounting by Hemmann as oblong-format ‘windows’ in larger upright leaves, as illustrated in Noorman 2019 (n. 1), p. 105, seems – contrary to the suggestion in Schwartz 1986 (note 3), p. 187 – essentially to preserve the original order. The numbering system of the library refers, first, to the upright leaf, then to the individual item nested within it, always counting in rows outward from the inner margin; recto and verso indications refer equally to both – hence on the page reproduced by Noorman, ‘233.5v’ represents the side of the fifth of the smaller oblong leaves visible on the larger page fol. 233v (counting, to the eye reading from the left, 2 1 4 3 6 5); somewhat confusingly, the sixth item, to the left of no. 5, belongs to a subsequent leaf in Grossmann, the recto of which appears a page earlier as no. 6 on fol. 233r. Hemmann’s leaves accommodate mostly two original leaves each of Album amicorum I, six of Album amicorum II, with the rather unbalanced result that Grossmann’s albums occupy fol. 94-210 and 211-235 of the convoluut, respectively. For convenience, I shall preface folio references with the album to which they belong.

- Zeisold’s funeral announcement (Rector Academiae Ienensis … Et si quidem Diogenes, Jena 1643) occupies a large oblong sheet intended for posting; for a description, reproduction, and list of surviving exemplars see Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachraum erschienenen Drucke des 17. Jahrhunderts (VD 17) (www.vd17.de), VD17 547:622659U (catalogue numbers cited hereafter in this format without further preface). H. Lauterwasser, Angst der Höllen und Friede der Seelen. Die Parallelvertonungen des 116. Psalms in Burckhard Großmans Sammeldruck von 1623 in ihrem historischen Umfeld (Abhandlungen zur Musikgeschichte 6), Göttingen 1999, esp. pp. 17-18 and 367, has drawn attention to a manuscript account of Grossmann’s life in the compendious Athenae Salanae of the seventeenth-century Jena chronicler Adrian Beyer (vol. 15, Jena, Thüringer Universitätsbibliothek und Landesbibliothek, Ms. Prov.q.28a, fol. 327r-v; my thanks to Johanna Triebe of the Jena library for providing information and a reproduction); this depends, however, almost word for word on Zeisold – or did Beyer, who had served as Grossmann’s tutor (see Lauterwasser, p. 1), wrote a poem for him on his departure from Jena in 1624 and another on his wedding (see notes 18 and 35 below), signed his first album on 3 January 1631 (Album amicorum I, fol. 170.1r), and, according to Zeisold, heard Grossmann’s confession, in fact supply the essential text for Zeisold?

- The reference to his birthplace as ‘Vinas’ in Schwartz 1986 (note 3), p. 186, rests on a misreading of the designation ‘Vinariensis’, or ‘Vinariensis Thuringensis’, that accompanies his name in several places.

- On Burchard Grossmann the Elder see Lauterwasser 1999 (note 8), esp. pp. 1-17; also L. and K. Hallof (eds.), Die Inschriften der Stadt Jena bis 1650 (Die Deutschen Inschriften 33), Berlin 1992, pp. 189-190.

- Since Benesch, however, the distinction between them appears to have faded from view: Noorman 2019 (n. 1), p. 105, and Royalton-Kisch 2012 (note 1) both give the son the father’s dates and, in the latter instance, biography – a mistake already recognized in advance by Schwartz 1986 (note 3), p. 186. See also note 53 below.

- See Lauterwasser 1999 (note 8), also Anguish of Hell and Peace of Soul (Angst der Hellen und Friede der Seelen), Compiled by Burckhard Grossmann (Jena, 1623): A Collection of Sixteen Motets on Psalm 116 by Michael Praetorius, Heinrich Schütz, and Others, ed. C. Wolff with D. R. Melamed (Harvard Publications in Music 18), Cambridge, Mass. 1994.

- See Zeisold 1643 (note 8), and Lauterwasser 1999 (note 8), pp. 6 and 17. I cite dates according to the place involved. Grossmann’s part of Germany still held to the Julian calendar; Holland had already adopted the Gregorian. In tracing Grossmann’s itineraries I assume old-style dating unless otherwise indicated.

- Burchard the Younger called himself his father’s only son on the grave he endowed for the elder Grossmann in the Johanneskirche of Jena; see Hallof and Hallof 1992 (note 10), p. 190, and Rifkin 2011 (note 4), p. 161, note 41 (which mistakenly calls the son Bernhard). Neither of the principal biographical sources for the elder Grossmann cited by Lauterwasser 1999 (note 8), pp. 1, 367, and 378 – his will (Weimar, Thüringisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, Hofgericht Jena, Generalia 120, fol. 1r-15v) and the announcement of his funeral, also by Zeisold (Rector Academiae Ienensis Johannes Zeisoldus … Exsequias hodie eundum est … Dm. Burchardo Großmann, Jena 1637; VD17 547:622727Q) – mentions a child other than Burchard the Younger. The mother, Regina, had two surviving children by her deceased first husband; see Lauterwasser, p. 6, and Begräbnüß und Gedächtnüß Predigt, der ... Frawen Reginen ... Burchardi Großmans ... Haußfrawen, Jena 1625, fol. E4r and F4r. Although Burchard the Elder remarried in 1626 (ibid., pp. 11–12), he and his second wife, Anna Schröter, had no children, and she had none from her brief first marriage; see Praesentissimum Remedium ... bey Christlicher Leichbestattung des ... Herrn Johannis Schröteri, Jena 1615 (VD17 7:713938T), fol. C3r. See also note 52 below.

- See G. Erler (ed.), Die jüngere Matrikel der Universität Leipzig 1559-1809. Als Personen- und Ortsregister bearbeitet und durch Nachträge aus den Promotionslisten ergänzt, 3 vols., Leipzig 1909 (Codex diplomaticus Saxoniae regiae 16-18), vol. 1, Die Immatrikulationen vom Wintersemester 1559 bis zum Sommersemester 1634, p. 149; and G. Mentz in collaboration with R. Jauernig (eds.), Die Matrikel der Universität Jena, vol. 1, 1548 bis 1652 (Veröffentlichungen der Thüringischen Historischen Kommission 1), Jena 1944, p. 130. On such early enrolments see, among other sources, Erler, pp. LVII-LVIII.

- For Grossmann’s schooling see Zeisold 1643 (note 8); also Lauterwasser 1999 (note 8), p. 17.

- See Rifkin 2011 (note 4), p. 162, esp. note 46.

- See A. Beyer, Viaticum elegiacum … Dn. Burchardi Großmans Iunioris … abitum a docta Salana, Jena 1624 (VD17 23:701838A); for the professors’ inscriptions see Rifkin 2011 (note 4), p. 162, note 46.

- The last entries in Leipzig date from 9 and 10 January 1625 (Album amicorum I, fol. 109.1v; fol. 106.1r, 126.2r); entries resume, in Jena, on 20 January (fol. 186.1v; year added by Grossmann) or 5 April (fol. 149.2r). For the visit to Dresden, also a possible brief return to Jena during the summer of 1624, see Rifkin 2011 (note 4), p. 162 – where, however the folio number cited in note 47 as 121.4r should read 124.1r.

- Between January 1625 and June 1629 Album amicorum I records only the following – obviously very brief – stays elsewhere (references separated by a semicolon give outer dates): 7 August 1625, Weimar (fol. 187.2r; see also note 51 below); 6-7 January 1626, Torgau (fol. 113.1r; fol. 136.2r); 11 March 1626, Lobeda (fol. 154.1v); and finally visits to Weimar 1 April 1626 (fol. 117.1r), 15 November 1626 (fol. 119.1r), 30 May 1628 (fol. 195.1v), 29 March 1629 (fol. 143.1v), and 23 April 1629 (fol. 188.2v). Of these destinations, only Torgau does not lie in the immediate vicinity of Jena; did Grossmann again spend some time in Leipzig, not far from Torgau? In biographical notes added to both alba amicorum (I, fol. 94.1r; II, fol. 211r), Hemmann wrote that Grossmann studied law. Hemmann clearly took most or all of his information about Grossmann from the albums themselves; but I have not yet located the entry or entries from which he drew this assertion. See also note 53 below.

- For Grossmann’s itinerary before Nuremberg and Altdorf see below. For his matriculation at Altdorf see E. von Steinmeyer (ed.), Die Matrikel der Universität Altdorf, 2 vols. (Veröffentlichungen der Gesellschaft für fränkische Geschichte, ser. 4, vols. 1-2), Würzburg 1912, pt. 1, p. 213, as well as pt. 2, p. 245. Grossmann reached Nuremberg by 28 March 1630 (Album amicorum II, fol. 234.2r); further entries for the period show him alternately in Nuremberg (3 May, fol. 219.5r), Altdorf (5 May, fol. 225.2r; 6 May, fol. 221.1v, 224.1r, 224.3v, 224.6v, 226.4v, 227.4v, 230.5v, 230.6v, 232.5v, 233.5r, 234.6v, 235.2v), Nuremberg (6 May, fol. 226.4v; 7 May, fol. 230.6r, 234.4r), and finally, from 16 May (fol. 229.3v) to 20 June (fol. 221.6v), Altdorf. On 6 May in Nuremberg he himself entered an inscription in the album of the patrician Georg Christoph Volckamer; see L. Kurras (ed.), Die Handschriften des Germanischen Nationalmuseums Nürnberg, 5 vols., Wiesbaden 1974-1994, vol. 5, Die Stammbücher, pt. 1, Die bis 1750 begonnenen Stammbücher (1988), p. 73, nos. 52 and 29. He returned Jena by 6 July (Album amicorum I, fol. 130.1r, 131.2v). See also Rifkin 2011 (note 4), p. 163, note 54; and notes 98 and 99 below.

- See Schnabel 2003 (note 5), p. 426.

- See Album amicorum II, fol. 234.6r (4 March 1630) and 229.4v (7 March 1630), Album amicorum I, fol. 166.1r (12 October 1630), and frequently afterwards.

- See, for example, Album amicorum I, fol. 185.1r (16 October 1630: ‘Dem Ehrenvesten, Vorachtbahrn vnd Mannhafften Herrn BURCKHARD GROSZMANN designirtem Fendrichen’), 170.1v (27 October 1632: ‘der löblichen studenten Compagnie Commandeur vndt Hauptmann’), and 124.2r (15 February 1641: ‘meinem fenrich’, signed ‘Nicol Rheiner Capitain Vnndt Paumeister’); on the rank of ‘Fendrich’ see the articles ‘Fähnrich’ and ‘Fähnlein’ in H. Frobenius, Militär-Lexikon Handwörterbuch der Militärwissenschaften, Berlin 1901, p. 194. In his biographical note to Album amicorum I (fol. 94.1r) Hemmann wrote that Grossmann served in the Saxe-Weimar militia. Although I see no reason to question this information – Weimar and Jena both belonged to the duchy of Saxe-Weimar – I also have yet to determine its basis.

- See, for ‘Artis et Martis’, Album amicorum I, fol. 179.1v (2 December 1639) and 204.2v (19 March 1641), similarly fol. 204.2r (24 May 1641) and 207.2v (19 January 1641), as well as note 34 below; for the others see, respectively, fol. 192.1v (28 February 1638), 210.1r (6 March 1644), and 123.2r (15 July 1641). Although Schnabel 2003 (note 5), pp. 405 and 426-427, seems to interpret the frequent appearance of the motive ‘Arte et Marte’ in seventeenth-century albums as more often than not essentially symbolic in its meaning, its more concrete significance in connection with Grossmann seems to me inescapable.

- During this period, Album amicorum I documents only the following, brief, absences from Jena: 20-26 September 1630, Weimar (fol. 135.1v; fol. 121.2r); 26-27 April 1631, Thörey (fol. 185.1r; fol. 159.2r); 25-28 June 1632, Leipzig (see below); 14 June 1633, Weimar (fol. 159.1r).

- Following an entry of 5 May in Jena (Album amicorum II, fol. 231.5r), the album documents the following stops: 10 May, Leipzig (fol. 220.2v); 15 May, Zerbst (fol. 225.4r); 18 May, Magdeburg (fol. 228.1v); 24 May, Hamburg (fol. 230.2v); 17-21 June (n.s.), Amsterdam (fol. 223.2r + 223.1v, 230.3v; fol. 223.2v, 229.5v-229.6r); 3-7 July (n.s.), The Hague (fol. 222.5v; fol. 217.1r); 14-16 July (n.s.), Leiden (see note 100 below); 21-22 July (n.s.), ’s-Hertogenbosch (fol. 230.3v; fol. 234.5r, 234.5v); 26 July (n.s.), Wesel (fol. 233.6v); 2 August (n.s.), Düsseldorf (fol. 228.5v); 5 August (n.s.), Cologne (fol. 222.1v); 11 August (n.s.), Koblenz (fol. 227.4r); 12 August-11 September, Frankfurt am Main (fol. 220.3r; fol. 220.4r); 13-14 October, Eisenach (fol. 223.4r; fol. 220.6r, 229.5r); 15 October, Gotha (fol. 230.1r); 21 October, Erfurt (fol. 229.3r); 25-29 October, Weimar (fol. 230.2r; fol. 217.3r); 5 November, Jena (Album amicorum I, fol. 128.2v), immediately afterwards 19 November-8 December Bucha (fol. 229.4r; fol. 227.1r). Grossmann travelled to ’s-Hertogenbosch and perhaps beyond with a medical student from Breslau by the name of Joachim Elsner, who had held a disputation at Jena in March; see Album amicorum II, fol. 230.3v, and Elsner, Disputatio medica de angina, Jena 1634 (VD17 23:239587T). Not least because Elsner’s album entry lays special emphasis on the stretch from Hamburg to Amsterdam (‘vnser von Ham= | burg nach Amsterdam gethanen Reÿse’) we may presuppose a longer stay in the Hanseatic city than the single relevant entry in Album amicorum II attests. Indeed, even with ten ‘lost’ days for moving from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar, a notable amount of time separates that entry from the next one, of 17 June (n.s.) in Amsterdam; moreover, Hamburg represented a not inconsiderable detour on the way from Leipzig to Amsterdam – and to my knowledge nothing, despite the effects of the war, would have stood in the way of a more direct route like one through Braunschweig and Osnabrück.

- On the Convent of Frankfurt see W. Jesse, ‘Mecklenburg und der Prager Friede 1635’, Jahrbücher des Vereins für Mecklenburgische Geschichte und Altertumskunde 76 (1911), pp. 161-282, esp. pp. 186-205. Oxenstierna had signed Grossmann’s ‘home’ album two years earlier (Album amicorum I, fol. 98.1r, Jena, 6 December 1632).

- Grossmann seems not to have left Jena at all in 1635 or early 1636; a reference to Weimar in an entry of the former year (fol. 158.1r: ‘Vinariens:’; see also note 67 below) denotes the origin of the writer, not the place of writing.

- For a full itinerary and further details see Rifkin 2011 (note 4), pp. 163-165.

- See Rifkin 2011 (note 8), p. 164, note 64. Of the various definitions for ‘Hofmeister’ in J. and W. Grimm et al., Deutsches Wörterbuch, 17 vols. and index of sources, Leipzig 1854-1971, vol. 4, pt. 2 (1868–1877), cols. 1693-1694, I suspect no. 4, which stresses a role in the education of the family children (‘aufseher und bewahrer des gesindes und der kinder des hauses … auch erzieher der kinder’), best applies to Grossmann.

- Although Album amicorum I shows no entries from Jena securely datable before 29 July 1637 (fol. 160.2v), Grossmann surely arrived there within a day or two of a stop at Naumburg on 16 May (Album amicorum II, fol. 232.6r). For the death of his father see Zeisold 1637 (note 14); Hallof and Hallof 1992 (note 10), pp. 189-190; and Lauterwasser 1999 (note 8), pp. 14 and 17.

- The Jena matriculation book records the enrolment of a Burchard Grossmann, also from Weimar, in summer semester 1639; see Mentz and Jauernig 1944 (note 15) p. 130, also Schwartz 1986 (note 3), p. 186. In Leipzig, at least, a student did not have to re-matriculate to return to studies; see Erler 1909 (note 15), vol. 1, p. XLVII. Nevertheless, since Grossmann, himself an only child, did not have a son at the time – let alone one born in Weimar – this can only refer to him or to an as yet unidentified nephew or great nephew of Burchard the Elder.

- See Festivitati nuptiali viri arte & marte eximii, Dn. Burchardi Grosmans/ cum … Dorothea Maria, viri ... Dn. Henrici Glasers … filia, Jena 1641(VD17 15:747627Q); and Zeisold 1643 (note 8). Grossmann had spent the day before in Weimar; see Album amicorum I, fol. 124.2r.

- See Festivitati nuptiali (note 34), esp. fol. A4r and B1r; and Album amicorum I, fol. 204.1v, 205.1r, 205.1v, and 205.2v (Heinrich Glaser, Gera, 14 March 1641); a further member of the bride’s family contributed an entry to Album amicorum I on 19 March (fol. 202.4v).

- Except for what look like brief visits to Jena in July 1641 (fol. 123.2r), October 1641 (fol. 172.2r-v, 183.1r-v), and June 1642 (fol. 188.1r-v), every entry in Album amicorum I from March 1641 until shortly before Grossmann’s death comes from Gera.

- See Album amicorum I, fol. 206.1r (27 February 1645).

- Hemmann obviously fell into some confusion concerning Grossmann, writing that he died single and in straitened circumstances (Album amicorum I, fol. 94r: ‘in Ziemlicher dürfftig- | keit’; Album amicorum II, fol. 211r: ‘lediger weiße V. sonder Vermögen’); on Grossmann’s title page to Album amicorum II, moreover, he added a notice reading ‘†. Gera, An(no). 16 .. |: nî fallor : | etliche 70.’ (fol. 211.1r).

- The biographical sketch in Zeisold 1643 (note 8) refers to Grossmann’s military career with the words ‘Militiam quoq; ex parte fuit sectatus’, that for his father in Zeisold 1637 (note 14) somewhat more fully, if not much more informatively: ‘à quo togatam partim, partim sagatam militiam sectato sua sibi commoda Respubl. pollicetur’.

- Weimar, Thüringisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, Hofgericht Jena, Generalia 120, fol. 3r (‘Meinem Sohn, habe Ich sein müßiges Leben, eine ge- | raume Zeitthero, Wöchentlich, mit Einem Tahler Kost- | gelde Verlohnen Vnd Besolden müssen’), 3v (‘Zur bezahlung eines Pferdes, auch meinem Sohne 20. Taler | Zahlen müßen’), 6r (‘mein einziger Sohn :/: deme Ich | Von seiner Kindheit ahn, nur privatim 22. Præcepto- | res unterhalten :/: Wohl Vnd Geistlich erzogen, | Zue den Studijs befördert, Vnd wo nicht bey denselben /: denn, hierinnen, hat er mich mit Unwahrheit aus- | getragen, Alß hette Ich einen großen Doctorem | aus ihme haben wollen :/ Jedoch bei der edlen | Schreibfedern erhalten’), and 7v (‘alle sein Großmütterlich Erbe | welches er so Vnnütze vnd Vergeblich mit Reisen, Zwe- | rung Vnd Müssig gangk durchgebracht’); also Lauterwasser 1999 (note 8), p. 17.

- Schwartz 1986 (note 3), p. 186, already called attention to the ‘distinguished people – rulers, military men, university professors, humanists, government officials, artists – [Grossmann] encountered in his travels’.

- See Rifkin 2011 (note 4), pp. 164-165.

- For the following see ibid., pp. 165-166; also D. Stauff, ‘Canons by Tobias Michael and Others in the Albums of Burckhard Grossmann the Younger’, Schütz-Jahrbuch 35 (2013), pp. 153-161.

- To the information on this tablature in Rifkin 2011 (note 4), p. 165, I might add that the Paulus Röder of Kochberg identified there as the possible composer surely had a family relationship – probably that of son and father – to the pastor of the same name and same city who published an attack on a Calvinist Bible translation (Biblia der H. Schrifft … auff die Prob gesetzt, Frankfurt am Main 1607; VD17 3:302216L) in the same year as my suggested Röder, clearly a younger man, enrolled at university in Jena. I should also correct the indication of lute tuning given in the earlier article, which omitted one course: it properly reads f′ d′ b@ g d A G F E@ D. My thanks for information on this and related points to John Griffiths, François-Pierre Goy, and Andreas Schlegel.

- See Schwartz 1986 (note 3), p. 186; while Schwartz refers only to the second album, the remark applies equally to both. For Heyblocq see J. Noorman, ‘“schatten van de konst”’. The Drawings Collection in the Album amicorum of Jacob Heyblocq (1623-1690)’, Delineavit et sculpsit 44 (December 2018), pp. 12-31.

- I should perhaps stress the distinction between the artists discussed here, insofar as we know their positions or activities, and the Briefmaler or Wappenmaler whom contributors often paid to enhance their inscriptions, most commonly with gouaches or painted coats of arms; cf. Schnabel 2003 (note 5), pp. 104-107, 345-346, and 474-476, also note 91 below. The enumeration that follows does not include such items, nor does it record sketches of military fortifications and the like. I also omit from consideration Johann Batista Kraus, known through an engraved battle scene of 1645 (Kurtze aber doch warhafftige Beschreibung; VD17 23:676180B), who signed Grossmann’s second album in Dresden (fol. 218.5v, 18 October 1636); since he did not include a drawing and identified himself as a former quartermaster to Count Mansfield, his presence may owe more to Grossmann as officer than to Grossmann as a devotee of art.

- See Album amicorum II, fol. 221.6r (‘Jörg Christoff Eimmardt burger Vnd Maler in Regenspu[rg]’, 4 July 1636), 224.5r (anon., s.l., s.d.; on parchment), 232.2r (Samuel Tewrer [?], s.l. 1636), 233.2v (s.l., s.d.), 232.4r (August Richter, Leipzig, 13 December 1636), 232.6v (Valltien Kurtz, s.l., s.d.), 234.1v (‘David Mentzel Mahlerge …’, s.l., s.d.), and 235.1v (‘Johann deuerling Mahler | in leipzig. Nach der belä = | gerung. i637 den 4 appril’). For August Richter (1608-1668) see A. Schröder, ‘Richter, August’, in U. Thieme, F. Becker, and H. Vollmer (eds.), Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, 37 vols., Leipzig 1907-1950, vol. 28 (1934), p. 283; for Eimmart (1603-1658) see ‘Eimmart, Georg Christoph’, in M. H. Grieb (ed.), Nürnberger Künstlerlexikon. Bildende Künstler, Kunsthandwerker, Gelehrte, Sammler, Kulturschaffende und Mäzene vom 12. bis zur Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts, 4 vols., Munich 2007, vol. 1, p. 329. The refractory signature that I read as ‘Tewrer’ could suggest, especially given the confluence of the year with Grossmann’s Viennese sojourn, an identification with Samuel Deyrer – known also as Teuer, Teirer, and similarly – a painter active in the Austrian town of Steyr; see H. Geissler, Zeichnung in Deutschland. Deutsche Zeichner 1540-1640, ex. cat. Stuttgart (Staatsgalerie) 1979-1980, 2 vols., vol. 2, pp. 126-127, who refers in turn to J. Wastler, Das Kunstleben am Hofe zu Graz unter den Herzogen von Steiermark, den Erzherzogen Karl und Ferdinand, Graz 1897, which I could not consult. The claims for inclusion in this company of Kurtz and the two nameless contributors rest not least on their adoption of the format – a full leaf with no, or at best a very minimal, inscription – typical of the professional artists, as well as the proximity of their drawings to most of the others, including that of Rembrandt (see note 2 above): Grossmann appears largely to have followed the common practice of reserving particular portions of his album for contributors of shared social or professional status; see Schnabel 2003 (note 5), pp. 137-139 and 551-553. With Kurtz, moreover, what looks like a fragmentary letter under his name could have formed part of an inscription identifying him as ‘Mahler’.

- See Album amicorum I, fol. 159.1v (‘Martin Thurschalla Maler’, Jena, 1 May 1636), 176.2r (‘friderich wil= | helm franck | Mahler’, s.l., s.d.), and 177.1r (‘Andreas Zeideler | Academic9 in ihena’, 1625). Martin Thurschalla, a member of a well-known family in Eisenach, matriculated at Jena in the winter semester of 1636; see Mentz and Jauernig 1944 (note 15), p. 333. According to Thieme, Becker, and Vollmer 1907-1950 (note 47), vol. 33 (1939), p. 502, he decorated the pulpit of a church in Bardowiek near Lübeck in 1655. See also fig. 7 and note 67 below. For Friedrich Wilhelm Franck see S. Gericke, ‘Franck, Friedrich Wilhelm’, in G. Meissner et al. (eds.), Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon. Die bildenden Künstler aller Zeiten und Völker, Munich 1983-, vol. 43 (2004), p. 447, to which I might add the following indications of activity in Arnstadt or its immediate surroundings: an epitaph of 1617 in the parish church of Witzleben (thanks to Claudia Marschner of the Schlossmuseum Arnstadt for the reference); an epitaph dated 1620 in the Oberkirche, Arnstadt (thanks to Oliver Bötefür of the Evangelische Kirchengemeinde Arnstadt for details on this painting); and a letter dated Arnstadt, 25 November 1629, in which Franck seeks payment from Count Günther XLII of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen for a grotto in the court palace at Arnstadt (Rudolstadt, Thüringer Stadtsarchiv, Kanzlei Arnstadt, 1601, fol. 1r-1v + 2v; my thanks to Helga Scheidt of the Schlossmuseum Arnstadt for the reference). Andreas Zeideler, from Jena, matriculated there with the designation ‘pictor’ in summer semester 1611; see Mentz and Jauernig, p. 373. The death date of 1632 supplied by Grossmann rules out an identification with the draftsman and engraver of the same name listed in Thieme, Becker, and Vollmer, vol. 36 (1947), p. 432; but we might plausibly imagine a family connection with the Wenzel Zeideler (1589-1642) from Kahla, near Jena, mentioned on the same page.

- See Album amicorum I, fol. 144.2r (anon., s.l., s.d.), 146.1v (anon., s.l., s.d.), 150.1r (anon., s.l., s.d., with inscription fol. 150.2v), 153.2r (anon., s.l., s.d.), 158.1r (‘N Goyer’, possibly ‘Coyer’, s.l., s.d.; the online catalogue of the Hague library implausibly reads the initial as ‘A’), 178.1v (Christian Braun, Jena, 14 April 1629), 179.2v (Johann Friedrich Lauhn, Jena, 2 December 1639), 180.1r (anon., s.l., s.d.), and 196.1v. (anon., s.l., s.d.); for all but the sixth of these items, the format corresponds to that described in note 47 above as typical of professional drawings. On Braun see Mentz and Jauernig 1944 (note 15), p. 31; for Lauhn see ibid., p. 180, and note 66 below.

- See Album amicorum I, fol. 193.1r (‘Andreas Bretschneider Maler’) and 198.2r (Hans Daniel Bretschneider), both Leipzig, 26 June 1632. For Andreas Bretschneider see F. Hinneburg, ‘Bretschneider, Andreas (III)’, in Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon (note 48), vol. 14, p. 157; and Geissler 1979-1980 (note 47), vol. 2, p. 185. According to Grossmann, both Bretschneiders died in 1632. See also below, fig. 8.

- See Album amicorum I, fol. 178.2r (‘Christian Richter Mahler’, Weimar, 7 August 1625), 178.2v (‘Jeremias Richter Mahler’, s.l., August 1630), and 179.1r (‘Christian Richter’, s.d., amplified by Grossmann with ‘Iunior | Weimmar’ and subsequently a cross and the date ‘i637’). On the court painter Christian Richter see E. Mentzel, ‘Christian Richter und die anderen Altenburger Glieder der thüringischen Künstlerfamilie Richter’, in Mitteilungen der Geschichts- und Altertumsforschenden Gesellschaft des Osterlandes 15/1 (1938), pp. 126-145; and E. Jeutter, ‘Christian Richter in den Kunstsammlungen der Veste Coburg’, in M. Eissenhauer (ed.), Die Waschung des Naaman im Jordan. Christian Richter (1587-1667). Dokumente zum Leben und Werk des Weimarer Hofmalers, Coburg 1999, pp. 15-57, esp. 15-27. Mentzel, p. 141, gives the younger Richter’s year of birth as 1621. His undated drawing most likely comes from Grossmann’s visit to Weimar in 1633 or, just possibly, one in the years 1628-1630 (see notes 20 and 26 above); no doubt because of his youth, his father appears to have signed for him – compare the signature with that of the father both on fol. 178.2r and in further examples reproduced in Jeutter, pp. 34-35. For previously documented activity of Jeremias Richter – at Frankfurt am Main in 1644-1645 and at Jena (including a portrait of Johannes Zeisold) in 1650-1651 – see W. Scheidig, ‘Richter, Jeremias’, in Thieme, Becker, and Vollmer 1907-1950 (note 47), vol. 28 (1934), p. 292; and Die Porträtsammlung der Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel, ed. P. Mortzfeld (portraits.hab.de, accessed 15 January 2021) under A 24735 and A 21862; both the attribute ‘Mahler’ and the entry of the drawing on the reverse of the leaf containing that of Christian Richter the Elder affirm his identity with the brother of the latter baptized at Altenburg on 18 September 1591 (Mentzel, p. 128) – and surely exclude the otherwise conceivable identification with the Jeremias Richter (1609-1651), also from Altenburg, who matriculated at Jena in summer semester 1629 and later became a clergyman in the nearby town of Kosma; for this Jeremias see Mentz and Jauernig 1944 (note 15), p. 260, and Ultimum Christi patientis suspirium … als der abgelebte Cörper des ... Jeremiae Richters … ist beygesetzet worden (VD17 39:107892G).

- Richter’s dedication begins, ‘Meinem Viehlgünstigen lieben | Herrn Schwagern’; for his and Grossmann’s families see, respectively, Mentzel (note 51) and note 14 above. For the broader meaning of ‘Schwager’ see Grimm 1854-1971 (note 31), vol. 9 (1894–1899), cols. 2176-2181, at cols. 2176-2177, under no. 2.

- See J. S. Held, ‘Rembrandt’s Aristotle’, in idem, Rembrandt’s “Aristotle” and Other Rembrandt Studies, Princeton 1969, pp. 3-44, at p. 43, note 151, or idem, Rembrandt Studies, Princeton 1991, pp. 17-58, at p. 57, note 151; and Schwartz 1986 (note 3), p. 186. Not everyone has followed this lead: N. Courtright, ‘Origins and Meanings of Rembrandt’s Late Drawing Style’, Art Bulletin 78 (1996), pp. 485-510, at p. 489, calls Grossmann a jurist, while F. Lammertse and J. van der Veen, Uylenburgh & Son. Art and Commerce from Rembrandt to De Lairesse, 1625-1675, exh. cat. Amsterdam (Museum Het Rembrandthuis/London (Dulwich Picture Gallery) 2006, p. 52, describe him as a ‘scholar’ – an identification echoed, perhaps because of the misconception about Grossmann’s age (see note 11 above), in Noorman 2019 (n. 1), p. 105, and Royalton-Kisch 2012 (note 1).

- See note 20 above.

- For Christoph Grossmann see Album amicorum I, fol. 189.2v (Leipzig, 25 June 1632: ‘Seinem So Wohl Von gemuht als geblüht | Sehr trewenn Sonderlichen Freunde’), and Album amicorum II, fol. 219.2v (Leipzig, 5 November 1636), where he calls himself ‘Kauffmann’.

- I base this information principally, but not entirely, on VD 17 (note 8).

- Insofar as I could examine the curricula vitae in an admittedly smaller sample of funeral sermons for which I had access to the complete text – a sample, however, that also includes material not covered in VD 17 (note 8) – I cannot find evidence of any merchant’s having attended university.

- See Schwartz 1986 (note 3), pp. 186-187.

- See ibid.

- For princes and princes’ children see the entries of the following in Album amicorum II, all on pages dated 1634 without indication of place: Frederik Hendrik of Orange (fol. 214.5v); Johann Ernst of Saxe-Eisenach (fol. 212.3r + 212.4r); Albrecht and Ernst of Saxe-Weimar (later Saxe-Eisenach and Saxe-Gotha, respectively; both fol. 213.3r); Johann Moritz and Heinrich of Nassau-Siegen (fol. 222.4r); Friedrich I of Hesse-Homburg (fol. 216.4r); Johann Ludwig, the teenaged son of Johann II of Pfalz-Zweibrücken (fol. 213.2r); Ernst von Brandenburg, the teenaged son of Johann Georg of Brandenburg (fol. 213.4r); and the three surviving sons of the Winter King Friedrich von der Pfalz, Karl Ludwig (fol. 212.5r), Moritz (fol. 212.6r), and Eduard (fol. 213.1r). For Joachim de Wicquefort see fol. 229.5v-229.6r (Amsterdam, 21 June).

- See, in Album amicorum II, the entries of Joachim Friedrich von Blumenthal (fol. 222.2v, 29 August), Laurentius Braun (fol. 221.4v, 25 August), Sylvester Braunschweig (fol. 222.3v, 6 September), Johannes Dehnart (fol. 220.3r, 12 August), Franciscus Eulenhaubt (fol. 222.5r, 23 August), Georg Franzkius (fol. 221.3v, s.d.), Siegmund von Holtzen (fol. 218.6v, 28 August), Matthias Kleist (fol. 222.4v, 7 September), Andreas Lar (fol. 226.1v, 8 September), Jonas Mastorski (fol. 220.3v, 3 September), Melchior Nering (fol. 235.6r, 4 September), Valentin Purgollt (fol. 220.4r, 11 September), Balthasar Rinck (fol. 225.6r, 8 September), Andreas Rorsch (fol. 222.3r, 30 August), Christoph Rüger (fol. 227.6v, 14 August), Abraham von Sebottendorf (fol. 221.4r, 24 August), Gabriel Tünzel (fol. 219.4v, 21 August), and Hans von Zeidler alias Hofmann (fol. 218.2r, 21 August).

- J. Zunckel, Rüstungsgeschäfte im Dreißigjährigen Krieg. Unternehmerkräfte, Militärgüter und Marktstrategien im Handel zwischen Genua, Amsterdam und Hamburg (Schriften zur Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte 49), Berlin 1997, pp. 46-47. I owe my thinking about a possible connection between Grossmann’s voyage and matters of arms to Schwartz 1986 (note 3), p. 186, and discussions with Benjamin A. Rifkin.

- So far as I can tell, however, the identification by Schwartz 1986 (note 3), p. 186, of ‘many’ among those who contributed entries to Album amicorum II as ‘builders and designers of fortifications’ rests more on inference from the nature of some sketches in the book than from information provided by the signatures. Needless to say, drawings of military structures or implements could simply reflect the interests of a soldier.

- Grossmann’s itinerary in 1636 could suggest a military or political background as well, including as it does stays in Vienna, Prague, and Dresden, the capitals of the principal allies against France and Sweden, and in Nuremberg, a major player in arms manufacture and dealing. For the general situation and the roles of Saxony and the Empire see, for example, C. V. Wedgwood, The Thirty Years War, London 1938, pp. 386-391, 395, and 407; or E. W. Zeeden, Das Zeitalter der Glaubenskämpfe 1555-1648 (Handbuch der deutschen Geschichte 9), Stuttgart 1970, pp. 108-109. For Nuremberg see A. Schütze, ‘Waffen für Freund und Feind. Der Rüstungsgüterhandel Nürnbergs im Dreißigjährigen Krieg’, Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte 45/2 (December 2004), pp. 207-224.

- Schwartz 1986 (note 3), p. 186. I should stress that Schwartz advances this notion very cautiously.

- Of the drawings, only that of Christian Richter the Elder has such an inscription directly accompanying the image (see note 52 above), while that of Lauhn (see note 49 above) has an inscription on the facing verso page (fol. 179.1v) to which Grossmann added the annotation ‘pictii [?] & scrip:’.

- See note 48 above; the earlier inscription dates from 1635. The figure of Hercules clearly derives from Adriaen deVries’s fountain in Augsburg depicting the same subject, although the lower part of the drawing could suggest the mediation of Jan Muller’s print after de Vries – for which see J. P. Filedt Kok, ‘Jan Harmansz. Muller as Printmaker – III. Catalogue’, Print Quarterly 12 (1995) pp. 3-29, at pp. 22-23. Thurschalla departs from both sources, however, in depicting the later phase in the conflict when Hercules has already deprived the beast of all but one of its heads.

- See notes 47 and 50 above. The inscription added to the page with Deuerling’s drawing bears the date 2 May 1637, that on the reverse of Richter’s 23 December 1637; the inscriptions added to Bretschneider’s page come from 1639, 1640, and an uncertain date between 1632 and 1638.

- On visits to artists’ studios by art lovers in Holland see E. van de Wetering, ‘Rembrandt’s Beginnings – an Essay’, in idem and B. Schnackenburg (eds.), The Mystery of the Young Rembrandt, exh. cat. Amsterdam (Museum Het Rembrandthuis)/Kassel (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister) 2001-2002, pp. 22-57, at pp. 31-34; and Van de Wetering, ‘Rembrandt as a Searching Artist’, in Rembrandt. Quest of a Genius, exh. cat. Amsterdam (Museum Het Rembrandthuis)/Berlin (Gemäldegalerie) 2006, pp. 79-123, at pp. 95-96.

- See note 55 above.

- See note 50 above, and Album amicorum I, fol. 102.1r (Jacob Freiherr von Windischgrätz), 148.1v (Rudolphus Hanisius), and 189.2r (Marcus Chemniz, ‘Ephorus’ of Windischgrätz); for Hanisius Jacob von Windischgrätz see Erler 1909 (note 15), vol. 1, pp.161 and 510 respectively. Given Andreas Bretschneider’s date of birth, estimated at ca. 1578 (cf. note 50 above), I wonder if we should not imagine Hans Daniel as a son or nephew closer in age to Grossmann – and also his primary contact among the pair.

- See Album amicorum I, fol. 142.2v (Christian Michael) and 187.1v (Elias Freystetter); Erler 1909 (note 15), vol. 1, pp. 293 and 117, respectively; and, further on Michael, Rifkin 2011 (note 4), p. 166, note 76; Stauff 2013 (note 43), p. 160; and W. Steude, ‘Michael’, in L. Finscher (ed.), Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Allgemeine Enzyklopädie der Musik, 2nd. ed., Kassel 1994-2008, Personenteil, vol. 12, cols. 158-163, at col. 161.

- See Album amicorum I, fol. 127.2v.

- For a larger, if temporally somewhat distant, context for Michael’s canon see R. C. Wegman, ‘Musical Offerings in the Renaissance’, Early Music 33 (2005), pp. 425-437.

- Grossmann’s attributes inevitably recall those of Jan Visscher Cornelisen, the standard bearer in Rembrandt’s Nightwatch – on whom see, most fully, S. A. C. Dudok van Heel, ‘Frans Banninck Cocq’s Troop in Rembrandt’s Night Watch. The Identification of the Guardsmen’, The Rijksmuseum Bulletin 57 (2009), pp. 42-87, at pp. 53-54 and 78-79, notes 48-64.

- Benesch 1963 (note 2), p. 19. Benesch added, in explanation, ‘Rembrandt is the only artist among the 144 entries’ – an assessment obviously not based on first-hand examination and, indeed, appropriated simply from C. Hofstede de Groot, Die Urkunden über Rembrandt (1575-1721) (Quellenstudien zur holländischen Kunstgeschichte 3), The Hague 1906, p. 32.